Corals

Biodiversity

Cold-water coral reefs provide a home for many other animals and they are among the most diverse ecosystems in the ocean – more than 1300 species have been found living amongst cold-water corals in the NE Atlantic alone, and specialists often discover new species that have never been described before.

Here we look at a few examples of some animals commonly found living among cold-water corals. Click the images below for more information and follow the Go Deeper links for more pictures:

Sponges are distinguished from other metazoan animals in that they lack a true organisation of cells into body tissues, and by the presence of a unique aquiferous system. Most sponge cells are totipotent, meaning that one cell type can change into other cell types as the sponge requires. This is a distinct advantage: sponges can break into two or more individuals, each of which can regenerate into a new but genetically identical sponge, a form of asexual reproduction.

Sponges are sessile suspension feeders, and most species are marine. A sponge feeds by circulating seawater through its body’s aquiferous system, removing nutrients along the way before being expelled through the osculum. Some sponges have a rigid skeleton made of either calcium carbonate, silica or collagen.

The sponges associated with cold-water coral reefs are diverse: taxonomically, morphologically and ecologically. Over a hundred species inhabit the Lophelia reefs off western Scotland, and many new species are being discovered from cold-water coral reefs worldwide. Sponges often encrust the hard substrata within living reef frameworks and coral rubble habitats, and some species bore through the coral skeletal framework, which helps break down dead coral and contribute to mound formation. Large glass sponges (Class Hexactinellida) are particularly conspicuous on the reefs, forming delicate habitats themselves. Extensive areas of cold-water sponge reefs have recently been discovered off western Canada. The Porifera also exhibit a spectrum of bioactive chemicals with potentially pharmaceutical applications: the diversity they support and their socioeconomic value for humans must help to ensure the protection of both cold-water sponge and coral reef habitats.

- Beuck L, Freiwald A, Taviani M (2009) Spatiotemporal patterns in deep-water scleractinians from off Santa Monica di Leuca (Apulla, Ionian Sea). Deep Sea Research II 57:458-470

- Conway KW, Barrie JV, Krautter M (2005) Geomorphology of unique reefs on the western Canadian shelf: sponge reefs mapped by multieam bathymetry. Geo-Marine Letters 25:205-213

- Conway KW, Krautter M, Barrie JV, Whitney F, Thomson RE, Reiswig H, Lehnert H, Mungov G, Bertram M (2005) Sponge reefs in the Queen Charlotte Basin, Canada: controls on distribution, growth and development. In Freiwald, A. and J.M. Roberts (eds), Cold-water Corals and Ecosystems. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 605-621

- Hogg MM, Tendal OS, Conway KW, Pomponi SA, van Soest RWM, Gutt J, Krautter M, Roberts JM(2010) Deep-Sea Sponge Grounds: Reservoirs of Biodiversity, Cambridge : World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP regional seas report and studies ; no. 189) (UNEP-WCMC Biodiversity Series ; 32)

- Reveillaud J, Remerie T, van Soest R, Erpenbeck D, Cárdenas P, Derycke S, Xavier JR, Rigaux A Vanreusel A (2010) Species boundaries and phylogenetic relationships between Atlanto-Mediterranean shallow-water and deep-sea coral associated Hexadella species (Porifera, Ianthellidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 56(1):104-14

- van Soest RWM, Beglinger EJ (2009) New bioeroding sponges from Mingulay coldwater reefs, northwest Scotland. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 89: 329-335

- van Soest RWM, Lavaleye MSS (2005) Diversity and abundance of sponges in bathyal coral reefs of Rockall Bank, NE Atlantic, from boxcore samples. Marine Biology Research 1: 338-349

Cnidarians are a diverse group of soft-bodied and sometimes calcified animals united by a common body plan of only two cell layers separated by a jelly-like mesoglea which provides structural support in the water. Many cnidarians can reproduce asexually and sexually, and can also display an “alternation of generations”, a life cycle characterized by an attached polyp phase and a free-swimming larva or medusa phase: thus, cnidarians encompass both sessile and mobile species. Most are suspension feeders, but some are also predators. Lophelia itself appears to have a flexible feeding habit, ingesting a variety of zooplankton prey and particulates.

Cold-water coral reef frameworks are comprised of scleractinian corals, but these habitats host diverse assemblages of other cnidarians, which, like sponges associated with Lophelia habitats, often display high degrees of genetic diversity and new species have been discovered. Hydroids, anemones, zonathids and octocorals encrust both living and dead coral fragments, and species often co-occur, indicating local environmental conditions. The upright growth habit and often delicate nature of many cnidarians including Lophelia make these animals highly vulnerable to activities such as bottom fishing.

- Arantes RCM, Castro CB, Pires DO, Seoane JCS (2009) Depth and water mass zonation and species associations of cold-water octocoral and stony coral communities in the southwestern Atlantic. Marine Ecology Progress Series 397: 71-79

- Cairns SD, Bayer FM (2009) A generic revision and phylogenetic analysis of the Primnoidae (Cnidaria: Octocorallia). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 629: 79 p

- Henry L-A, Nizinski MS, Ross SW (2008) Occurrence and biogeography of hydroids (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) from deep-water coral habitats off the southeastern United States. Deep-Sea Research I 55: 788-800

- Kitahara MV (2007) Species richness and distribution of azooxanthellate Scleractinia in Brazil. Bulletin of Marine Science 81: 497-518

- Lindner A, Cairns SD, Cunningham CW (2008) From offshore to onshore: multiple origins of shallow-water corals from deep-sea ancestors. PLoS ONE 3: e2429

- López-González PJ, Gili J-M, Williams GC (2001) New records of Pennatulacea (Anthozoa: Octocorallia) from the African Atlantic coast, with description of a new species and a zoogeographic analysis. Scientia Marina 65: 59-74

- Mortensen P.B., Buhl-Mortensen L., Gebruk A.V., Krylova E.M. (2008) Occurrence of deep-water corals on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge based on MAR-ECO data. Deep-Sea Research II 55: 142-152

- Moura CJ, Cunha MR, Schuchert P (2007) Tubiclavoides striatum gen. nov. sp. nov. (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa): a new bathyal hydroid from the Gulf of Cadiz, north-east Atlantic Ocean. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 87: 421-428

- Murillo FJ, Durán Muñoz P, Altuna A, Serrano A. (2010) Distribution of deep-water corals of the Flemish Cap, Flemish Pass, and the Grand Banks of Newfoundland (Northwest Atlantic Ocean): interaction with fishing activities. ICES Journal of Marine Science doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsq071

- Reveillaud J, Freiwald A, Van Rooij D, Le Guilloux E, Altuna A, Foubert A, Vanreusel A, Olu-Le Roy K, Henriet J-P (2008) The distribution of scleractinian corals in the Bay of Biscay, NE Atlantic. Facies 54: 317-331

- Watson JE, Vervoort W (2001) The hydroid fauna of Tasmanian seamounts. Zoologische Verhandelingen Leiden 334: 151-187

The Polychaeta is the largest class of the phylum Annelida – the segmented worms. Polychaetes are highly distinct from other worms. Each body segment often bears a pair of parapodia with stiff bristles known as setae protruding to the side. Setae are used in burrowing, crawling and swimming and some species harbour stinging poisons within their setae.

The heads of polychaetes are very morphologically diverse. Some, such as carnivorous worms, have a specialised proboscis which can evert to seize prey. The heads of mobile polychaetes also have a vast array of sensory organs, including eyes and sensitive tentacles. Others such as sessile filter-feeding polychaetes have a reduced sensory capacity but have long feathery extensions that are often ciliated and collect suspended food and passing plankton from the water column.

Numerous deep-sea studies have found polychaete worms to be among the most diverse and abundant organisms collected. In general, they are small-bodied, with a reduced number of segments compared to shallow water species.

- Fiege D, Barnich R (2009) Polynoidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) associated with cold-water coral reefs of the northeast Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea. Zoosymposia 2: 149-164

- Gillet P, Dauvin J-C (2003) Polychaetes from the Irving, Meteor and Plato seamounts, North Atlantic Ocean: origin and geographical relationships. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 83: 49-53

- Moen TL (2006) A translation of Bishop Gunnerus’ description of the species Hydroides norvegicus with comments on his Serpula triqvetra. Scientia Marina 70 S3: 115-123

- Roberts JM (2005) Reef-aggregating behaviour by symbiotic eunicid polychaetes from cold-water corals: do worms assemble reefs? Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 85: 813-819

The Crustacea is the largest subphylum of the phylum Arthropoda. The Crustacea includes the lobsters, crabs, copepods, shrimps and barnacles. Its members are characterised by a head with two pairs of sensitive antennae and three pairs of specialised mouthpart appendages which process food before it enters the mouth. They often have heavily armoured carapaces with a rigid exoskeleton made of chitin and other proteins. To grow, crustaceans must moult or shed their exoskeleton and produce a new one.

The Crustacea are a highly diverse group, including mobile and sessile forms that have a juvenile planktonic life stage. The majority of crustaceans are mobile and often travel great distances whilst feeding. They are generally scavenging organisms but some species are carnivorous and use their clawed appendages to crush and tear apart their prey. Highly specialised species such as barnacles are immobile and live attached to hard substrate within an enclosed series of calcium carbonate plates. Crustaceans are nearly as diverse as polychaete species on cold-water coral reefs.

- Buhl-Mortensen L, Mortensen P (2004) Crustaceans associated with the deep-water gorgonian corals Paragorgia arborea (L, 1758) and Primnoa resedaeformis (Gunn, 1763). Journal of Natural History 38: 1233-1247

- Di Geronimo R (2009) A new species of Gruvelialepas Newman, 1980 (Crustacea, Cirripedia) from the northern Atlantic and remarks on living and fossil closely-related genera. Zoosystema 31: 63-70

- Gheerardyn H, De Troch M, Vincx M, Vanreusel A (2009) Harpacticoida (Crustacea: Copepoda) associated with cold-water coral substrates in the Porcupine Seabight (NE Atlantic): species composition, diversity and reflections on the origin of the fauna. Scientia Marina 73: 747-760

- Myers AA, Hall-Spencer JM (2003) A new species of amphipod crustacean, Pleusymtes comitari sp. nov., associated with gorgonians on deep-water coral reefs off Ireland. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 83: 1029-1032

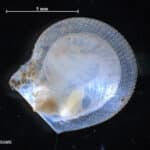

The Mollusca is one of the most successful phyla in terms of species richness and abundance with over 100,000 living species. Members of this phylum are very diverse with a range of forms including bivalves, gastropods, squid and octopus. Many molluscs are externally shelled, but some such as nudibranchs and aplaophorans are not.

Bivalves are distinguishable by two approximately symmetrical shells connected by a hinged region of calcified teeth and a tough ligament which springs the shell open. Large muscles counter this force and close the shell. Many soft-bottom dwelling bivalves have a large foot which can be used to move the shell, and some such as scallops can swim by forcing water through the siphon and others such as mussels attach to hard substrate using secreted material called byssal threads. Gastropods have a flattened foot muscle, topped by a shell with a single opening and an organic door known as an operculum. Most gastropods are detrital feeders but some can be carnivorous. Cephalopoda (squid and octopus) are complex molluscs with elaborate nervous and muscular coordination, high visual acuity, suckered arms and carnivorous feeding habits.

- García-Alvarez O, Salvini-Plawen LV, Urgorri V (2001) Unciherpia hirsuta a new genus and species of aplacophoran (Mollusca Solenogastres: Pararrhopaliidae) from Galicia, Northwest Spain. Journal of Molluscan Studies 67: 113-119

- García-Alvarez O, Salvini-Plawen LV, Urgorri V (2001) Unciherpia hirsuta a new genus and species of aplacophoran (Mollusca Solenogastres: Pararrhopaliidae) from Galicia, Northwest Spain. Journal of Molluscan Studies 67: 113-119

- Hoffman L, van Heugten B, Lavaleye MSS (2009) A new species in the family Yoldiidae (Bivalvia) from the Bay of Cadiz, northeastern Atlantic Ocean. Miscellanea Malacologica 3: 77-81

Members of the Phylum Echinodermata are often highly mobile components of the deep-sea. They include the Ophiuroidea (brittle stars and basket stars), Asteroidea (sea stars), Echinoidea (sea urchins) and Holothuroidea (sea cucumbers), but also the sessile stalked Crinoidea (crinoids). All echinoderms share a unique adult radial symmetry, with body structures often repeated in multiples of five, a common example being the arms of a star fish.

Echinodermata have a tough external leathery skin which encloses an internal skeleton comprised of interlocking calcium carbonate plates called ossicles. These calcareous plates can become strongly fused, such as in sea urchins to form an enclosed ball with openings for the mouth and other structures. Many species of Echinoidea are covered in spines and the outer skin is covered with pinching pedicellariae to ward off predators. The ossicles may also remain unfused in Echinodermata allowing the animal to be very flexible such as in sea stars and brittle stars.

Feeding behaviour in the Echinodermata is diverse, but many deep-sea species are omnivorous, feeding on a wide variety of different foods. In the Rockall Trough Ophiuroidea make up 27% of the echinoderm species collected, but numerically they far outnumber the remaining megafauna collected (63%). On cold-water coral reefs, Asteroidea have been observed predating upon coral polyps, and the reef habitat may also provide high quality habitat for sessile echinoderms such as crinoids.

- Allen Brooks R, Nizinski MS, Ross SW, Sulak KJ (2007) Frequency of sublethal injury in a deepwater ophiruoid, Ophiacantha bidentata, an important component of western Atlantic Lophelia reef communities. Marine Biology 152: 307-314

- Stöhr S, Segonzac M (2004) Deep-sea ophiuroids (Echinodermata) from reducing and non-reducing environments in the North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 84: 4722/1-20

The members of the phylum Bryozoa are almost exclusively colonial invertebrates, being comprised of small individual zooids growing in many different shapes such as runners, sheets, mounts, plates or trees. They are often mistaken for corals, sponges or even seaweeds. Bryozoan colonies arise from numerous asexually proliferated zooids. Each zooid is enclosed in a protective box-like exoskeleton, with apertures for ciliated feeding structures known as lophophores. Bryozoa are sessile suspension feeders.

Bryozoans have been discovered in great numbers and in an amazing diversity of morphological forms in the deep-sea. There are some large forms but most are small, fragile and rarely collected intact. Bryozoans can be rigid, with fused zooids forming strong erect branched forms. Soft ctenostome forms lack a rigid calcified skeleton. Ctenostome bryozoans are normally found on abyssal mud and illustrate how bryozoans have adapted to the deep-sea environment.

- Fernandez Pulpeiro E, Besteiro C, Ramil F (1988) Sublittoral bryozoans of the Norwegian Sea. Thalassas 6: 23-27

- Zabala M, Maluquer P, Harmelin J-G (1993) Epibiotic bryozoans on deep-water scleractinian corals from the Catalonia slope (western Mediterranean, Spain, France). Scientia Marina 57: 65-78