Corals

Cold-water coral morphology and reef structure

Cold-water corals are members of a large group, the Cnidaria, related to animals like sea anemones and jellyfish. Cold-water corals vary from solitary corals, a single polyp enclosed in a skeleton, to framework-forming colonial corals that form reefs themselves home to thousands of other animals. So far, only six species of cold-water coral have been found that can build framework reefs, compared to over eight hundred tropical species!

At first glance cold-water corals show no movement, living fixed in place. Looking closer, the minute polyps (usually just a few millimetres in diameter) are constantly outstretched, ‘feeling’ for passing prey and potential food. If a predator comes near, the polyps retract their tentacles rapidly back into the protection of the coral’s skeleton.

This section focuses on the skeletons and reefs formed by scleractinian or stony corals.

Looking at cold-water corals, like Lophelia, initially reveals a structure that is dominated by a branching limestone skeleton. Moving closer in and hundreds of tiny polyps become visible, with their flexible tentacles extended to catch passing food. The tentacles are the most obvious feature of the polyp, with species like Lophelia having up to 16 tentacles surrounding the polyp’s single opening – which serves both as a mouth and anus.

Like sea-anemones and other cnidarians, the tentacles of cold-water corals contain specialised stinging cells called nematocysts. These cells can immobilise prey by injecting a potent poison. Some corals only produce a mild sting, causing an itchy rash, whilst others are very dangerous, especially to people who could suffer an allergic reaction to the sting.

Cold-water coral skeletons lay the foundations of large reefs, supporting many thousands of individual polyps. On the other end of the scale, the single polyp of a solitary species provides a cup in which the coral polyp sits – in fact these species are often called ‘cup corals’.

The skeletons of corals offer several key advantages to the coral polyps. The hard structure provides a ready made shelter growing throughout the life time of the coral. The skeleton offers protection from predators, it lifts the live polyps clear of the seabed and into a position in the water currents where they are more likely to capture their prey.

Skeletons of scleractinian corals are made from calcium carbonate in the form of the mineral aragonite and develop from the basal disc of the polyp. The skeleton grows outwards, increasing the size of the skeleton. As new polyps grow, the skeleton increases in complexity, with new branches and axes forming.

The cold-water corals Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata (pictured to the left) can be thought of as primary and secondary reef framework-building species. Lophelia pertusa is a primary framework-building coral, which produces large, highly branched bushy colonies with branches that join together where they touch (‘anastomose’). This structure is incredibly strong, producing a long-lasting reef framework. Madrepora oculata produces a more delicate skeleton, with slender branches that form a so-called secondary reef framework. Madrepora is often found on Lophelia reefs in the north-east Atlantic ocean.

The reefs formed by Lophelia and other coral species develop over many hundreds or thousands of years. The upper levels of reefs support more recent coral growth with the densest accumulations of live Lophelia on the summit and upper slopes. The polyps work tirelessly keeping themselves clear of sediment, leaving the upper levels of the reef clean and pristine (See image of Lophelia reef on left).

But the live coral is just the tip of the iceberg, below lies the reef framework formed from the skeletal remains of previous generations of coral polyps. Over time this skeletal framework traps sands and muds to form a robust cold-water coral reef – ultimately these portions of the reef become home to the highest number of species (see the darker parts of the colony pictured left where other animal species can be seen).

The final outer portion of the reefs is often dominated by aprons of coral rubble extending around the reef. The coral rubble are the remains of the once living reef, broken apart by a combination of physical disturbance and the bioerosion of other animals that bore into the coral skeleton. The rubble habitats can extend for many metres around the base of the coral reef providing several sub-habitats.

The term ‘reef’ comes from an old Norse seafaring term ‘rif’ – a submerged structure rising from the seafloor that’s hazardous to shipping. These structures might be rock ridges, sandbanks or tropical coral reefs. Reefs create distinctive patches on the seafloor that trap sands and mud. Over time they develop to form structures rising from the surrounding seafloor that provide habitat for other species.

As cold-water coral reefs form at great depths they obviously do not represent a navigational hazard, but they do meet other criteria by which we define a reef. This is born out in legal as well as scientific definitions of the term. For example, the European Union’s Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC, 1996) states a reef can be a submarine, biogenic concretion which arises from the seafloor and which supports a community of animals. The cold-water corals, Lophelia pertusa, Goniocorella dumosa, Oculina varicosa and Solenosmilia variabilis all form reefs according to this definition.

- Wilson JB (1979) Patch’ development of the deep-water coral Lophelia pertusa (L.) on Rockall Bank. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 59: 165-177

- Freiwald A, Wilson JB, Henrich R (1999) Grounding Pleistocene icebergs shape recent deep-water coral reefs. Sedimentary Geology 125 (1-2): 1-8

Microbiology is actually a fundamental part of coral biology. Just as humans have beneficial bacteria (on our skin and in our intestines, without which we would not be healthy), so do corals. There may be thousands of species of microorganisms associated with each coral, performing a delicate balance of coordinated services. Some of the ways these microbes can help the coral are by breaking down waste products, recycling nutrients, and fending off other potentially harmful microbes by producing antibiotics or just by occupying the available space.

Deep-sea or cold-water corals live in dark, cold, high-pressure environments. The microbial communities of these corals are adapted to this extreme environment and so are likely to contain interesting bacteria that are new to us. Identifying and characterising those bacteria will not only increase our understanding of microbial diversity, but could also uncover a new source of enzymes or pharmaceuticals.

Techniques – seeing the unseen, how do we look at coral-associated microbes?

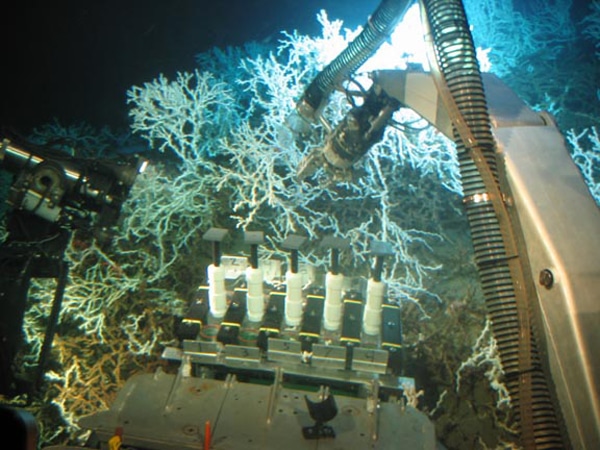

The first and most important issue is that microbes are everywhere in the ocean. Like a doctor during surgery, we need to keep any collection equipment very clean so that we are not adding foreign microbes to the coral. Deep-sea coral samples can be collected by a trawl, dredge, or by a submersible or remotely operated vehicle (ROV). In many of these cases, multiple corals may be combined in a single container. This is not acceptable for microbiological studies since one coral’s microbial community could contaminate another’s when they touch. Similarly, contact with sand or clay from the bottom, other animals, or even seawater from a different depth, could contaminate the coral samples. The cold-water corals must also be protected against changes in temperature between the sea floor and the surface, since temperature changes could cause a shift in the coral-associated microbial community. Ideally, coral samples for microbiology should be collected in an insulated container that has separate, sealed compartments for each individual sample.

Classical microbiology is based on the ability to grow microbes on nutrient agar (a semi-solid gel of microbial food). Growing microbes means you can take them back to the laboratory and study them – identify them based on certain genes, and characterise them by testing their metabolic and biochemical capabilities. This method is relatively easy and inexpensive. The downside is that microbes can be picky eaters, so each type of nutrient agar (and there are hundreds) will only grow a small percentage of the microbes that are on the coral. Some microbes are so finicky, we can’t figure out how to get them to grow at all yet.

The other way we can study microbes (especially the ones that don’t like to grow on agar) is to extract their DNA directly from the coral and then use molecular (genetic) techniques to identify them. This can be done using targeted fluorescent probes to count certain microbial groups, or by creating libraries of sequences from the coral-associated microbes and then comparing those sequences to a database of sequences from previously described (“known”) microbes.

Results – what does microbiology tell us?

Each coral species is essentially a separate microbial universe, so studying just one type of coral (like Lophelia pertusa) doesn’t tell us everything we need to know. There are more species of corals in the deep-sea than there are in shallow tropical systems, and so far the bacterial associates of only a handful (less than 15) of deep-sea species have even begun to be characterised. What’s more, bacteria aren’t the only microbes associated with corals; there are also archaea, fungi, and protists. We know essentially nothing about those groups in deep-sea corals.

Why do we need to know about the coral-associated microbes? Coral diseases are caused by microbes; either invading pathogens or when some stressor destabilises the balance between the coral and it communal microbes. In order to know what has gone wrong when disease occurs, it helps a lot to know how the system functions when it is working properly.

Another reason is that the coral’s associated microbes are its first line of adaptation to change. The microbiome (all the genetic capabilities of all the coral associated microorganisms) can be altered in response to environmental stresses on the order of hours to days, compared to decades or centuries for genetic adaptations to manifest in the coral animal. Understanding coral microbiology, in terms of microbial-species diversity as well as metabolic capabilities, is critical to determining the resiliency of deep-sea corals to climate changes such as increasing water temperatures and ocean acidification.

Lophelia microbiology, a global picture

Lophelia is a globally distributed coral but so far microbiological studies have been limited to a few places in the Atlantic: Norwegian fjords, the Mediterranean Sea, Rockall Bank (northwest of the United Kingdom) and the Gulf of Mexico. These studies have shown that there is variability in the Lophelia-associated bacterial communities; variation exists between coral’s colour morphs (red/orange versus white), and both within and between sampling locations. This diversity may be due to diet or other environmental factors.

However, underlying the spatial variability observed, there are Lophelia-specific bacterial symbionts. Identical sequences for two bacterial types have been found associated with corals sampled in both the Gulf of Mexico and a Norwegian fjord. We don’t know what these bacterial groups do for the coral (or vice versa), but there must be a significant reason for them to be conserved across the Atlantic ocean basin. Loss of these symbionts may be a sign of stress.

Bacterial groups associated with Lophelia include some types commonly found on shallow-water corals. There are also psychrophiles, “cold-loving” bacteria that are usually found in polar waters.

Videos

Description: Viosca Knoll, Gulf of Mexico, 2004; filmed using the Johnson-Sea-Link.

Running time: 8m46s

Copyright:USGS/Christina Kellogg

- Brück TB, Brück WM, Santiago-Vázquez LZ, McCarthy PJ, Kerr R, G. (2007) Diversity of the bacterial communities associated with the azooxanthellate deep water octocorals Leptogorgia minimata, Iciligorgia schrammi, and Swiftia exertia. Marine Biotechnology 9: 561-576

- Gray MA, Stone RP, McLaughlin MR, Kellogg CA (2011) Microbial consortia of gorgonian corals from the Aleutian islands. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 76: 109-120

- Hall-Spencer JM, Pike J, Munn CB (2007) Diseases affect cold-water corals too: Eunicella verrucosa (Cnidaria: Gorgonacea) necrosis in SW England. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 76: 87-97

- Hansson L, Agis M, Maier C, Weinbauer MG (2009) Community composition of bacteria associated with cold-water coral Madrepora oculata: within and between colony variability. Marine Ecology Progress Series 397: 89-102

- Kellogg CA, Lisle JT, Galkiewicz JP (2009) Culture-independent characterization of bacterial communities associated with the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75: 2294-2303

- Neulinger SC, Gärtner A, Järnegren J, Ludvigsen M, Lochte K, Dullo W-C (2009) Tissue-associated “Candidatus Mycoplasma corallicola” and filamentous bacteria on the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia). Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75: 1437-1444

- Neulinger SC, Järnegren J, Ludvigsen M, Lochte K, Dullo W-C (2008) Phenotype-specific bacterial communities in the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia) and their implications for the coral’s nutrition, health, and distribution. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74: 7272-7285

- Penn K, Wu D, Eisen JA, Ward N (2006) Characterization of bacterial communities associated with deep-sea corals on Gulf of Alaska seamounts. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 72: 1680-1683

- Schöttner S, Hoffmann F, Wild C, Rapp HT, Boetius A, Ramette A (2009) Inter- and intra-habitat bacterial diversity associated with cold-water corals. The ISME Journal 3: 756-759

- Sfanos K, Harmody D, Dang P, Ledger A, Pomponi S, McCarthy P, Lopez J (2005) A molecular systematic survey of cultured microbial associates of deep-water marine invertebrates. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 28: 242-264

- Webster NS, Bourne DG (2007) Bacterial community structure associated with the Antarctic soft coral, Alcyonium antarcticum. FEMS Microbiology Ecolgy 59: 81-94

- Yakimov MM, Cappello S, Crisafi E, Trusi A, Savini A, Corselli C, Scarfi S, Giuliano L (2006) Phylogenetic survey of metabolically active microbial communities associated with the deep-sea coral Lophelia pertusa from the Apulian plateau, Central Mediterranean Sea. Deep Sea Research 53: 62-75