Corals

Ecology

Ecology is a wide ranging field, which studies how living organisms relate to and interact with their surroundings. To put it more simply, ecology deals with how living organisms go about their daily business such as feeding, moving, fighting or mating.

The ecology of deep-sea organisms including Lophelia is very difficult to study. Biologists can’t conduct the usual type of experiments which would show how this species interacts with others and their surroundings. Instead much of our knowledge stems from observations either by ROV and video or from manned submersibles. Unfortunately, much is largely theorised based on past research on more accessible organisms, such as tropical coral reefs.

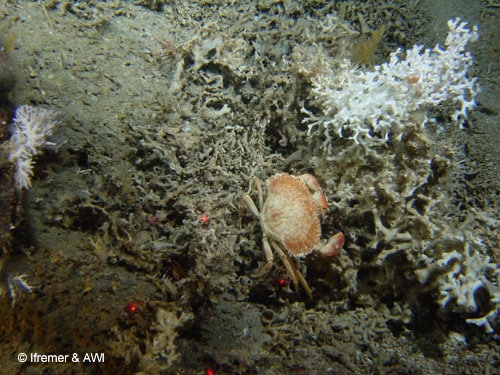

The ecology of a reef system is immensely complicated, with many thousands of different animals all going about their business. Some are predatory, whilst others eat away at the coral framework, breaking down larger parts into smaller ones. Here we summarise some of the available information on the ecology of a cold-water coral reef. Much of the published work is concentrated upon Lophelia pertusa reefs and that is reflected here.

Unlike many species of tropical corals, cold-water corals feed by snatching prey out of the water column. They have a series of tractable tentacles which drape loosely in the water as the polyps wait for the food to come to them. Cold-water corals are sessile, they don’t move in the search for food. Therefore they are often found in areas with a high current speed and a plentiful food supply. Seafans and other cold-water species are often found orientated to the direction of current flow, increasing the amount of prey which gets washed past and into the waiting polyps.

Each polyp of Lophelia has 16 tentacles, they use them like nets, waving them in the moving water. When a food particle or animal touches a tentacle, specialised cells called nematocysts inject a stunning poison into the prey. The prey is rendered immobile, and the polyp gently moves the prey into its mouth. Lophelia is generalist in its food preference, it will eat almost anything. In the laboratory it has been observed taking live zooplankton such as chaetognaths, small crustaceans and larger species such as krill. It has also been shown that Lophelia will take dead food particles of several different fish species. If it didn’t like it, it would spit it out and try the next one. Sometimes, unsuitable food or dirt can float into the tentacles, the coral can push it out and begin waiting for the next particle.

The growth of the coral skeleton of Lophelia pertusa colonies has been estimated to range between 4-25 millimetres per year, corroborated by reports of colonies growing on man-made structures (5-26 mm per year). Some species of tropical corals grow at rates upwards of 100 to 200 mm per year, but most massive framework forming tropical corals grow at rates similar to Lophelia.

Some Lophelia reefs are estimated to be over 8,000 years old, some settling in iceberg plough marks made during the last ice age. Lophelia reefs develop in two distinct phases, the living zone is only very young compared to the dead coral framework which supports the cap of living corals. Some scientists have recorded the living zone of Lophelia colonies within the northeast Atlantic to rarely exceed 20 living polyp generations which can attain a height ranging from 20 to 35 centimetres.

Gorgonian corals such as Paragorgia do not form reefs, instead they form a single large colony which can live for 100 to 200 years. It is clear that the low growth rates and long-life of corals may have severe conservation issues if any damage is incurred. Some scientists have remarked that damage caused now may not recover within our life-time.

Many organisms are restricted to a particular geographical area by the surrounding physical environment, for example polar bears are highly adapted to cold, Arctic conditions and would struggle to survive in the deserts of the Sahara and vice versa for lions and tigers. Corals suffer from the same restrictions, they are possibly restricted to local areas, by the surrounding substrate, food supply or intolerance to physical changes in temperature.

Cold-water corals are found in many of the world’s oceans, many species attain high densities in areas away from the influence of coastal seawater, preferring an environment with a stable salinity and temperature regime. They occur in a wide range of different depths, but nearly all are found below the depth which light can penetrate, and below the storm wave base which can damage corals. Being a passive suspension feeder, nearly all corals occur in areas with a high speed bottom current flow, bringing food and being strong enough to remove any sediment which may potentially smother the coral.

Molecular genetics and cold-water corals

The use of genetic techniques to study deep-sea organisms has increased significantly in recent times. These techniques provide the basis for an unseen science; invisible to the naked eye, these hidden genetic patterns can now be unraveled using the techniques of molecular genetics.

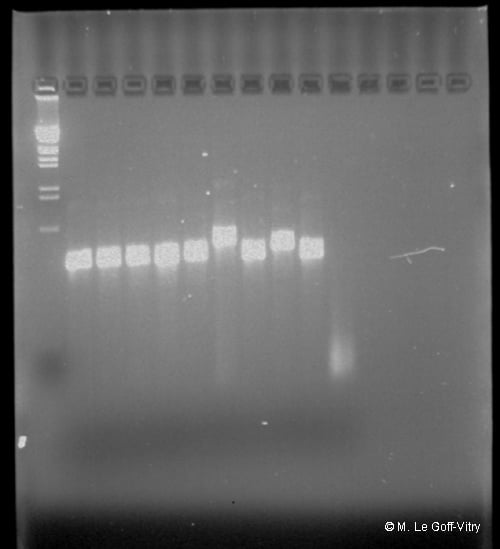

This approach became widespread with the development of gel electrophoresis, a versatile technique for separating molecules by characteristics such as size, shape or isoelectric point, it is often used as a precursor for more time consuming and focused techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Using these and other techniques, scientists can investigate the relationships between different species or even members of the same species by using common gene sequences.

The power of this new science allows scientists to study differences among species and between members of the same species. These techniques have been used to show that seemingly cosmopolitan species found in the deep-sea are actually groups of closely related species which are each restricted in their distribution. More recently, these techniques have shown that key cold-water coral species such as Madrepora oculata may be incorrectly described.

What do genetics tell us?

Molecular methods can be applied to target a variety of biological and ecological questions. Some molecular markers can provide useful information to infer evolutionary relationships among species and higher taxonomic ranks. This is crucial to understand how biodiversity is structured and how best it can be preserved over the long term.

Other molecular markers can be used to target populations at a defined geographical scale. Precious information about several fundamental aspects of the biology of a species can be obtained. For example, understanding how genetic diversity is distributed, if and how populations are connected via larval dispersal is essential to create meaningful conservation management strategies. This information also helps us understand the health of a population in a particular area – for example in terms of coral biology by understanding the proportion of sexual versus asexual reproduction. This information is essential for the design of marine protected areas.

Differences in deep-sea corals

After sequencing a particular region of the DNA extracted from different corals, it is possible to assess their similarity. This raw information can be used to draw a phylogenetic tree retracing the hypothetical evolutionary history of the different corals. Such an approach was applied on a wide range of DNA sequences from coral species, including cold-water corals. It revealed that morphological characters used to define the family into which Lophelia is classified might not provide sufficient resolution to describe evolutionary relationships within that family. At the level of the species, Lophelia showed a high genetic variability across the Atlantic Ocean, as sequences obtained from samples of Lophelia from the NE Atlantic were very different from those obtained from samples collected in the SW Atlantic.

Surprisingly, another widespread cold-water coral species, Madrepora oculata did not group with other species from its morphological family. Such results show that molecular approaches can be a useful alternative approach to traditional morphological taxonomy to understand how deep-sea corals relate to each other and with their tropical counterparts.

NE Atlantic Corals

Other molecular techniques can be used to investigate deep-sea coral populations at different geographical scales. Lophelia samples collected in Scandinavian fjords appeared to be genetically different from those distributed along the European continental margin. Results also suggest that continental margin reefs might originate from migrants dispersed out of the fjords in the past.

By using very variable molecular markers called micro-satellites, it is possible to gain very high resolution information about coral populations, even at the scale of a particular reef, about genetic diversity, larval exchanges among reefs and the levels of sexual and asexual reproduction. Such investigations revealed very varied profiles of populations across the NE Atlantic with some populations showing much higher genetic diversity, while others showed a much higher proportion of asexual than sexual reproduction.

On a wider-scale, larval dispersal seemed to be restricted locally around reefs, even if sporadic dispersal could occur between the continental margin populations. Fjord populations appeared very distinct from one another and from the continental margin populations.

- Baco AR, Shank TM (2005) Population genetic structure of the Hawaiin precious coral Corallium lauuense (Octocorallia: Corallidae) using microsatellites. In: Freiwald A, Roberts JM (Eds) Cold-water Corals and Ecosystems

- Le Goff MC, Rogers AD (2002) Characterization of 10 microsatellite loci for the deep-sea coral Lophelia pertusa (Linnaeus 1758). Molecular Ecology Notes 2: 164-166

- Le Goff-Vitry MC, Rogers AD, Baglow D (2004) A deep-sea slant on the molecular phylogeny of the Scleractinia. Molecular Phylogenetics 30(1): 167-177

- Le Goff-Vitry MC, Pybus OG, Rogers AD (2004) Genetic structure of the deep-sea coral Lophelia pertusa in the northeast Atlantic revealed by microsatellites and internal transcribed spacer sequences. Molecular Ecology 13(3): 537-549