Corals

The animal

The word coral conjures images of tropical waters with colourful reefs within snorkelling distance of the shore. These are tropical corals and are among the most studied and loved ecosystems on earth. It may surprise people to hear that corals aren’t just found in the tropics. The cold, dark waters of the deep-ocean are home to cold-water coral reefs.

Since the early 1800s scientists have known about corals and coral banks in the deep-sea. Many reports came from fishermen who brought back coral specimens which had become entangled in their nets – capturing the attention of scientists with the promise of these tantalizing glimpses of a hidden coral world.

Since these pioneering days, deep-sea science has advanced significantly. The development of tools ranging from acoustic mapping systems to mini-submarines has allowed scientists to visit cold-water corals in their natural habitat. Scientists have now recorded over 1,300 species living among coral reefs in the north-eastern Atlantic, proving them to be among the most important and diverse ecosystems of the world.

Cold-water corals are widely distributed and found in many parts of the world’s oceans. The Atlantic, Mediterranean, Indian and Pacific Oceans have all been found to contain cold-water corals. So far, many of the reports have been from the north-east Atlantic, where much of the current research has been undertaken.

What are cold-water corals?

There are several types of cold-water coral but they all belong to a group of animals called the Cnidaria. They are closely related to sea anemones, and like sea anemones they live fixed in place and feed by catching prey with their stinging tentacles. Corals are composed of polyps each having a ring of tractable tentacles surrounding a mouth.

As corals cannot move, they extend their sticky tentacles into the water column, hoping to grab a potential meal from the water currents. Corals can use a wide variety of food, including dissolved organic matter and the tiny animals and plants that live in the ocean currents (the plankton).

Some species of coral live as individuals forming a single polyp, while others are colonial which form colonies of many hundreds or thousands of polyps. Colonial corals build large, complex skeletons, usually from calcuim carbonate (limestone). Some species can eventually produce elaborate branching frameworks which over time can grow to become the basis of cold-water coral reefs.

Reef-building corals are very important in the deep-sea environment as they create and modify the surrounding habitat, producing many more places for other animals to live and hide. This in turn increases the abundance and diversity of animal life on the reef, making cold-water coral reefs biodiversity hot-spots in the deep-ocean.

Within the Cnidaria there are four major groups of animals:

(1) The Anthozoa including true corals, anemones and sea pens – nearly all the major cold-water coral species are anthozoans

(2) The Cubozoa, which are box jellies

(3) The Hydrozoa, with siphonophores, hydroids and fire corals

(4) The Scyphozoa, better known as jellyfish.

Cold-water corals belong to two groups, the Anthozoa and the Hydrozoa.

The Anthozoa includes colonial stony corals (Scleractinia), true soft corals (Octocorallia) and black corals (Antipatharia). The Hydrozoa includes the calcifying lace corals (Stylasteridae).

- Cold-Water Corals – the biology and geology of deep-sea coral habitats Published by Cambridge University Press Also available from Amazon.com and other retailers

- The biology, distribution and conservation status of cold-water corals are discussed in detail in the 2004 United Nations Environment Programme report “Cold-water Coral Reefs: Out of Sight – No Longer Out of Mind”. Visit UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Website Download PDF Report (High quality 17mb, Low Quality 2mb)

- The Hexacorallians of the World website is a compilation of publications concerning taxonomy, nomenclature and geographic distribution of extant hexacorallians.

- In 2005 summaries of research into cold-water corals were published in the book ‘Cold-water Corals and Ecosystems’ edited by André Freiwald and J Murray Roberts.

- The biology of Lophelia pertusa and other cold-water corals has been reviewed by A.D. Rogers in 1999 and forms an excellent place to start for in-depth data on many aspects of cold-water coral biology:

- Rogers, A. D. (1999). “The biology of Lophelia pertusa (LINNAEUS 1758) and other deep- water reef-forming corals and impacts from human activities.” International Review Of Hydrobiology 84(4): 315-406.

Where can you find corals?

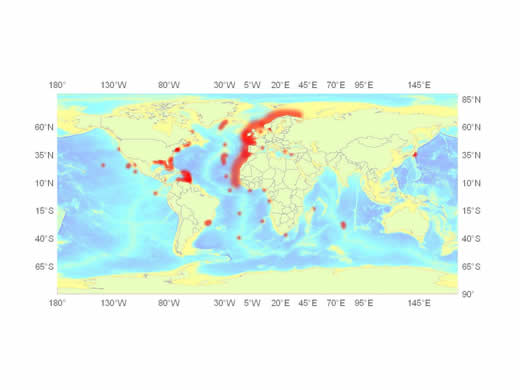

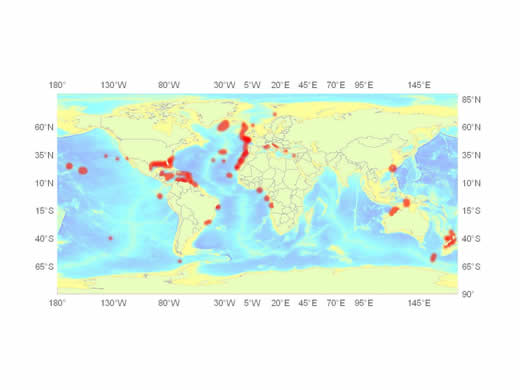

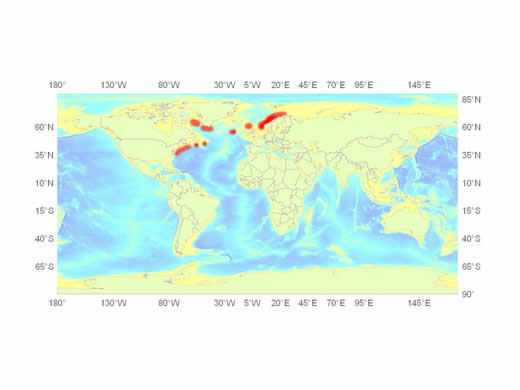

Many cold-water coral species are widely distributed, found throughout many of the world’s oceans. This type of distribution is scientifically termed cosmopolitan, and includes species such as Lophelia pertusa, Madrepora oculata and Paragorgia arborea among others. Some species have a more restricted distribution, for example, Gonicorella dumosa has only been found in the southern hemisphere, particularly in New Zealand waters.

Cold-water coral reefs develop over long periods of time, usually hundreds and for the larger reefs, thousands of years. Some reefs on the Sula Ridge in Norway are thought to have developed at the end of the last ice age, some 10,000 years ago. The deep-sea is a low energy environment, the corals grow very slowly and the presence of a reef usually indicates a stable, low disturbance environment.

The majority of cold-water coral reefs have been found in the northeast Atlantic Ocean, and are usually dominated by Lophelia. The largest reef complex in the world, the Sula Ridge Complex, was found off the Norwegian coast, it is over 14 km long and grows up to 35 metres from the sea bed. Closer to the United Kingdom there are many reefs along the continental shelf and offshore banks such as Rockall and the Porcupine Seabight. Recently, scientists discovered Lophelia growing on the legs of some North Sea Oil Rigs.

Throughout the world, cold-water corals appear to be adapted for particular environments. They are exclusively marine, found in areas away from the influence of coastal seawater either in the deep-sea or the deeper waters of fjords, with the highest aggregations appearing to be related to the presence of oceanic water masses.

They are usually found below the photic zone, between 200 and 400 metres, but the shallowest found so far was at 40 metres and the deepest at well over 1,000 metres. Corals are found in areas with a topographically enhanced bottom current, which serves several purposes. Firstly, the current will have scoured mobile sediments from the area, revealing areas of hard substrate suitable for coral settlement. Secondly, the fast currents limit the amount of sediment deposition on existing reefs. Thirdly, the currents deliver a constant food supply to the waiting corals.

The upper depth limit of corals may be restricted by the level of the seasonal storm wave base. These heavy surges occur as storms develop on the surface and can cause damage to the slow growing reef.

World-wide distributions of key species:

Lophelia pertusa (after Freiwald et al, 2004)

Madrepora oculata (after Freiwald et al, 2004)

Paragorgia arborea (after Tendal, 1992)

- Programme report “Cold-water Coral Reefs: Out of Sight – No Longer Out of Mind”.

Website

PDF Report (High quality 17mb, Low Quality 2mb) - Lophelia pertusa:

Mortensen PB, Hovland M, et al (2001) Distribution, abundance and size of Lophelia pertusa coral reefs in mid-Norway in relation to seabed characteristics. Journal of Marine Biological Association UK 81: 581-597 - Wilson, JB (1979) The distribution of the coral Lophelia pertusa (L.) [L. prolifera (Pallas)] in the north-east Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 59: 149-162

- Davies AJ, Wisshak M, Orr JC, Roberts JM (2008)Predicting suitable habitat for the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia). Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 55(8):1048-1062

- Paragorgia arborea:

Grasshof M (1979) Zur bipolaren Verbreitung der Oktokoralle Paragorgia arborea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Scleraxonia). Senckenbergiana Maritima 11: 115-137 - Tendal OS(1992) The north Atlantic distribution of the octocoral Paragorgia arborea (L., 1758) (Cnidaria, Anthozoa). Sarsia 77: 213-217

- Sanchez J (2005). Bubblegum corals from New Zealand seamounts and the deep sea. Water and Atmosphere, NIWA Publication 13(2)

- General:

Hall-Spencer J, Rogers A, Davies J, Foggo A (2007) Deep-sea coral distribution on seamounts, oceanic islands, and continental slopes in the Northeast Atlantic. Bulletin of Marine Science 81 (S1): 135-146 - Cairns SD (2007) Deep-water corals: an overview with special reference to diversity and distribution of deep-water scleractinian corals. Bulletin of Marine Science 81 (3): 311-322

- For an overview of research into cold-water corals see the 2005 book edited by André Freiwald and J Murray Roberts ‘Cold-water Corals and Ecosystems‘, and the recent book ‘Cold-water corals; the biology and ecology of deep-sea coral habitats‘

Key species

Here are four important cold-water corals – browse the site to learn more about these and other key species of cold-water coral.

Lophelia pertusa

Lophelia is the most widespread reef-framework forming cold-water coral. It has been frequently found in the North Atlantic Ocean, but it is still being discovered in oceans throughout the world where it’s robust skeletons form massive deep-sea coral reefs.

Madrepora oculata

The genus Madrepora has produced several species, of these Madrepora oculata is associated with cold-water coral reefs. It is much more fragile than Lophelia and is often found among Lophelia colonies.

Paragorgia arborea

Paragorgia is a type of sea fan or gorgonian coral. They form amongst the largest individual cold-water coral colonies known, with a central trunk which can grow to 3 metres high. These corals form huge fan-like colonies, orientated across the direction of current flow to help the polyps catch their food.

Goniocorella dumosa

Goniocorella has not received the same research interest that other corals have. It is restricted to the southern hemisphere, and occurs mostly in New Zealand waters and on adjacent oceanic banks.

Cold-water corals are found throughout the world’s oceans, with some species, such as Lophelia pertusa or Desmophyllum dianthus, being found in every ocean around the globe. So when animals, like corals, are sessile (firmly attached in one place) how do they get from one ocean to another? This is where their reproductive strategies come in. Though the corals themselves do not get up and move around, their larvae can be carried in strong ocean currents from one place to another, sometimes covering many hundreds of miles before settling down turning into adult corals anchored in place. Once these corals are grown and produce their own larvae, the next generation can then be taken another great distance away, thus hop-scotching across the world’s oceans, spreading and creating new populations, that may later form new reefs and mounds.

For more information on the reproduction of cold-water coral, you can read about Rhian Waller’s work on coral spawning.

Male, female or both?

Some corals are gonochoric, meaning each individual is one sex, either male or female. Others are hermaphroditic, meaning they are both sexes, either at the same time (simultaneous) or one sex becomes another at some point in their life history (sequential if the switch happens once or a few times, or cyclical if it’s a continuous cycle).

Lophelia pertusa is gonochoric, with all of the polyps on a colony being the same sex, so we can say that a colony of Lophelia is either male or female. In some shallow water reef-building corals the polyps on a single colony can be different sexes, but this hasn’t been found in any deep-water species as yet. Caryophyllia cup corals are the only cold-water corals found to date that are hermaphrodites, though this life history strategy is common amongst tropical corals.

Sexual vs asexual

Corals can reproduce in two ways – asexually by making clones or sexually by fusion of sperm and egg. Asexual reproduction happens when an adult of any sex produces an exact genetic replica of itself, known as a clone. This can be done in several ways, either by budding off from the body of the main coral, by the production of asexual larvae that are then released into the water column, or (in reef-building species) even by small broken branches falling from the main colony, surviving and growing into new colonies.

Sexual reproduction involves males producing sperm that fertilizes a female’s egg, which then becomes a larvae. This can either happen within the body of the female (brooding) with larvae later released into the water column or fertilization can happen in the water column itself (spawning).

There are advantages and disadvantage to both of these forms of reproduction. Asexual reproduction only produces clones of corals that are already there, so does not shuffle genetic material as in sexual reproduction. Asexual reproduction also only allows for short distance dispersal. On the other hand, sexual reproduction does generate genetic diversity and leads to the production of larvae that can, in some species, travel great distances. However, in fast flowing ocean currents there are downsides to sexual reproduction; the chance of sperm and egg meeting is small and many larvae die before they can settle.

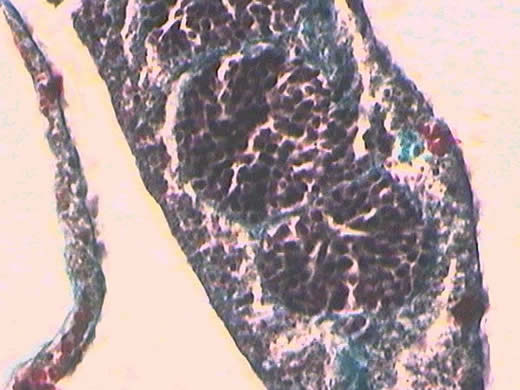

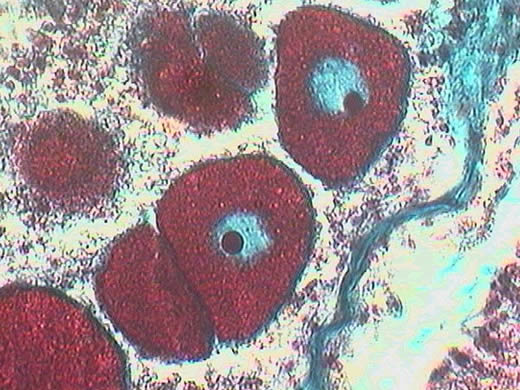

Slicing and dicing

So how do we study coral reproduction? There are many ways to do this. One important technique is known as ‘Histology’. Histology is used in many fields of research and gives us a way to look at the internal structure of an animal – it is particularly useful in medical science. We take the coral and decalcify it, that is to get rid of the skeleton using an acid, so that we can just look at the soft tissues. We then dehydrate the tissue using various grades of alcohol and embed the tissue in wax, creating a hard wax cube (see image to the left). We then slice up this cube, creating thin sections just a few microns thick through the coral, which we mount on a slide and stain various colours depending on what we want to look at. Looking at these thin sections under the high power microscope can tell us what sex the coral is, how many eggs are in a coral and even what stage of development the eggs and sperm are at.

There are other ways to examine coral reproduction too. If the eggs or sperm are large enough you can dissect them out and look at them under the microscope. The Transmission Electron Microscope or the Scanning Electron Microscope can also be used to look at how eggs and sperm are produced, or what the surface of a larva looks like. You can also collect corals and keep them alive in aquaria and wait for them to reproduce, then look for the larvae to describe and study them.

Why study reproduction?

By studying reproduction we can examine how a species has moved between different ocean basins. By looking at how larvae are produced, what time of year they are produced, and how long larvae can survive before settling we can start to understand to how far they can travel, and so which coral populations are connected along larval highways.

Reproduction is also highly stress dependent – very often a coral will stop reproducing when stressed – so we can use the reproductive status of coral populations to see how healthy they are. For example, we have found that no Lophelia corals from an area that had been trawled were reproducing sexually but in an untrawled area close by the corals were reproductive. This strongly suggests that stress to the corals in the trawled area was preventing them reproduce sexually.

- Brooke S, Young CM (2003) Reproductive ecology of a deep-water scleractinian coral, Oculina varicosa, from the southeast Florida shelf. Continental Shelf Research 23:847-858

- Burgess S, Babcock RC (2005) Reproductive Ecology of three reef-forming, deep-sea corals in the New Zealand region. In: Freiwald A, Roberts JM (eds) Cold-Water Corals and Ecosystems. Springer, New York, pp701-713

- Flint H, Waller RG, Tyler PA (2007) Reproduction in Fungiacyathus marenzelleri from 4100 m depth in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Marine Biology 151 (3): 843-849

- Waller RG, Baco-Taylor A (2007) Reproductive Morphology of Three Species of Deep-water Precious Corals from the Hawaiian Archipelago: Gerardia Sp., Corallium Secundum, And Corallium Lauuense. Bulletin of Marine Science, 81(3): 533-542

- Waller RG, Tyler PA, Smith C (2008) Fecundity and embryo development of three Antarctic deep-water scleractinians: Flabellum thouarsii, F. curvatum and F. impensum. Deep-Sea Research II, 55, (22-23):2527-2534

- Waller RG, Tyler PA, Gage JD (2005) Sexual reproduction of three deep water Caryophyllia (Anthozoa: Scleractinia) species from the NE Atlantic Ocean. Coral Reefs 24(4): 594-602

- Waller RG, Tyler PA (2005) The reproductive biology of two deep-sea, reef-building scleractinians from the NE Atlantic Ocean. Coral Reefs 24(3):514-522

- Waller RG (2005) Deep Water Scleractinians: Current knowledge of reproductive processes. In: Freiwald A, Roberts JM (eds) Cold-water Corals and Ecosystems. Springer, Heidelberg, 691-700

- Waller RG, Tyler PA, Gage JD (2002) The reproductive ecology of the deep-sea solitary coral Fungiacyathus marenzelleri (Scleractinia) in the NE Atlantic Ocean. Coral Reefs 21(4): 325-331