Locations

In this section we take a closer look at cold-water coral reefs around the world. They are amazingly colourful and form diverse habitats. As well as creating a home for many other species, cold-water coral reefs may also be important centres for speciation in the deep-sea. Click on the map below to visit some of the locations detailed in this section.

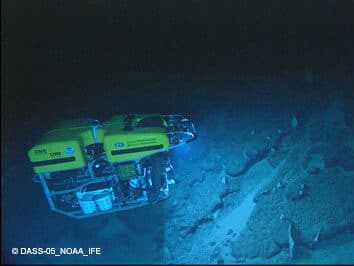

Only in the last few decades have cold-water corals been studied in detail. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries a few cold-water coral specimens were found by fishermen and early researchers. Due to technological limitations it was impossible to learn much more about them. In recent years, with the advent of manned submersibles and deep-sea remotely operated vehicles, our knowledge has increased significantly.

Navigate through this section to learn more about some of the pioneering research on cold-water corals, each section includes maps, images, videos and references to further information (follow the Go deeper links).

Arctic Ocean

Canadian Arctic

Very little is known about the cold-water corals of the Canadian Arctic: the deep-waters there simply remain largely unexplored, and much of the Arctic archipelago bathymetry remains to be mapped. However, rich coral assemblages have been identified in the Davis Strait, Baffin Island and Labrador Sea, which are predominantly gorgonians and black coral species likely associated with the meeting of the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans.

Corals also occur off Nunavut at approximately the shelf break. The Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, local communities and other stakeholders supported the DFO-proposed closure in 2008 of a restricted area otherwise fished for Greenland halibut.

Atlantic Ocean

Norway

Current status

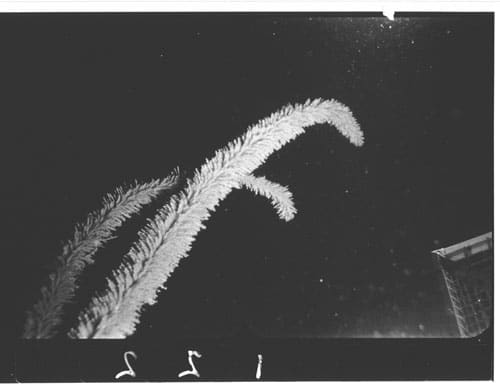

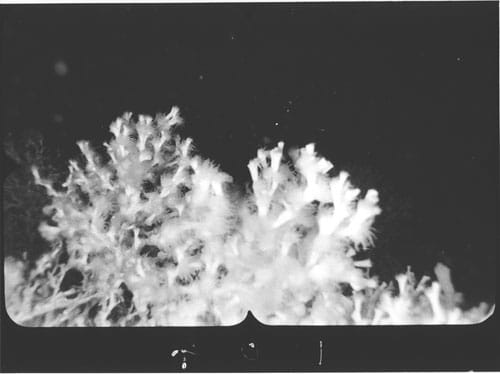

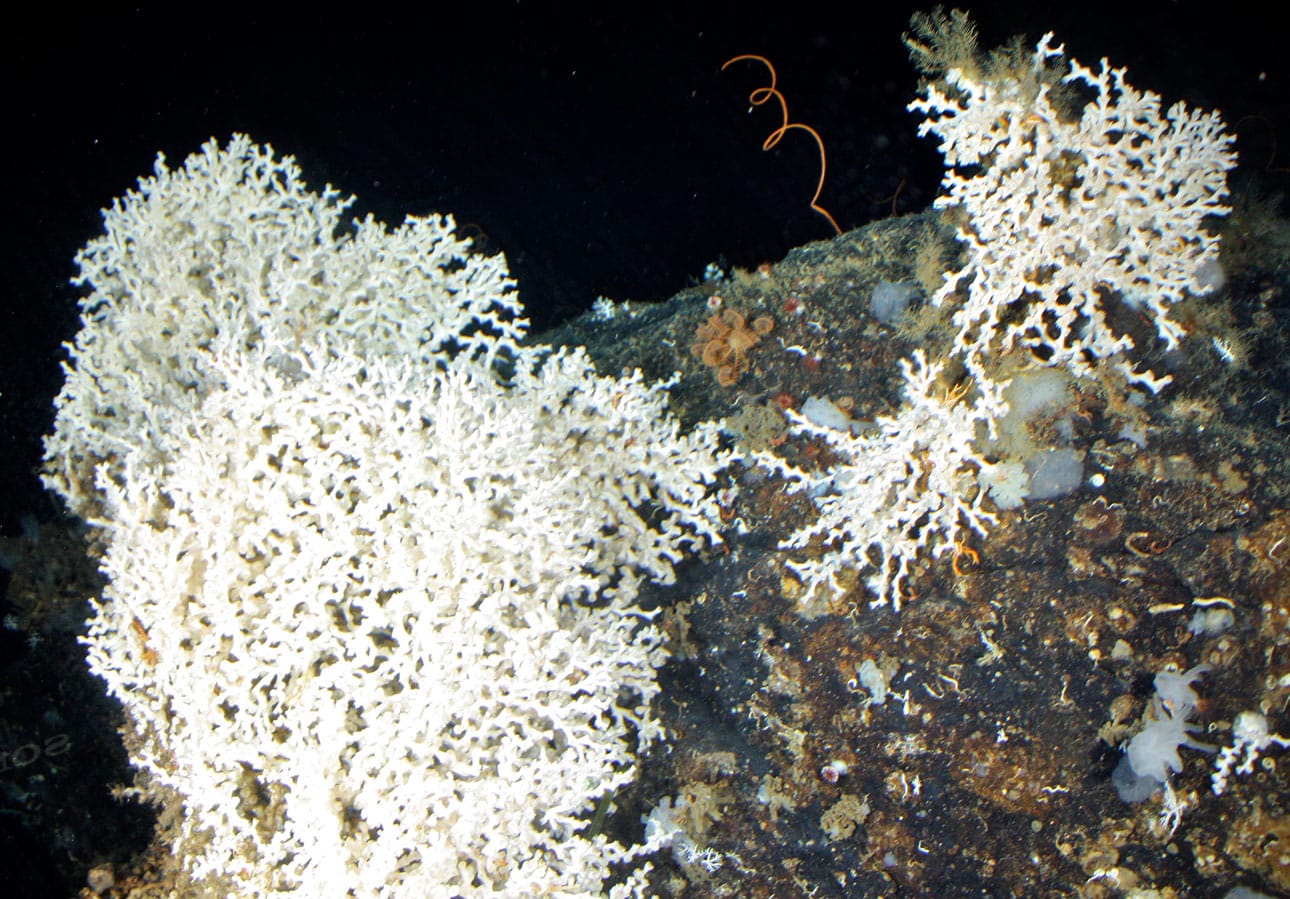

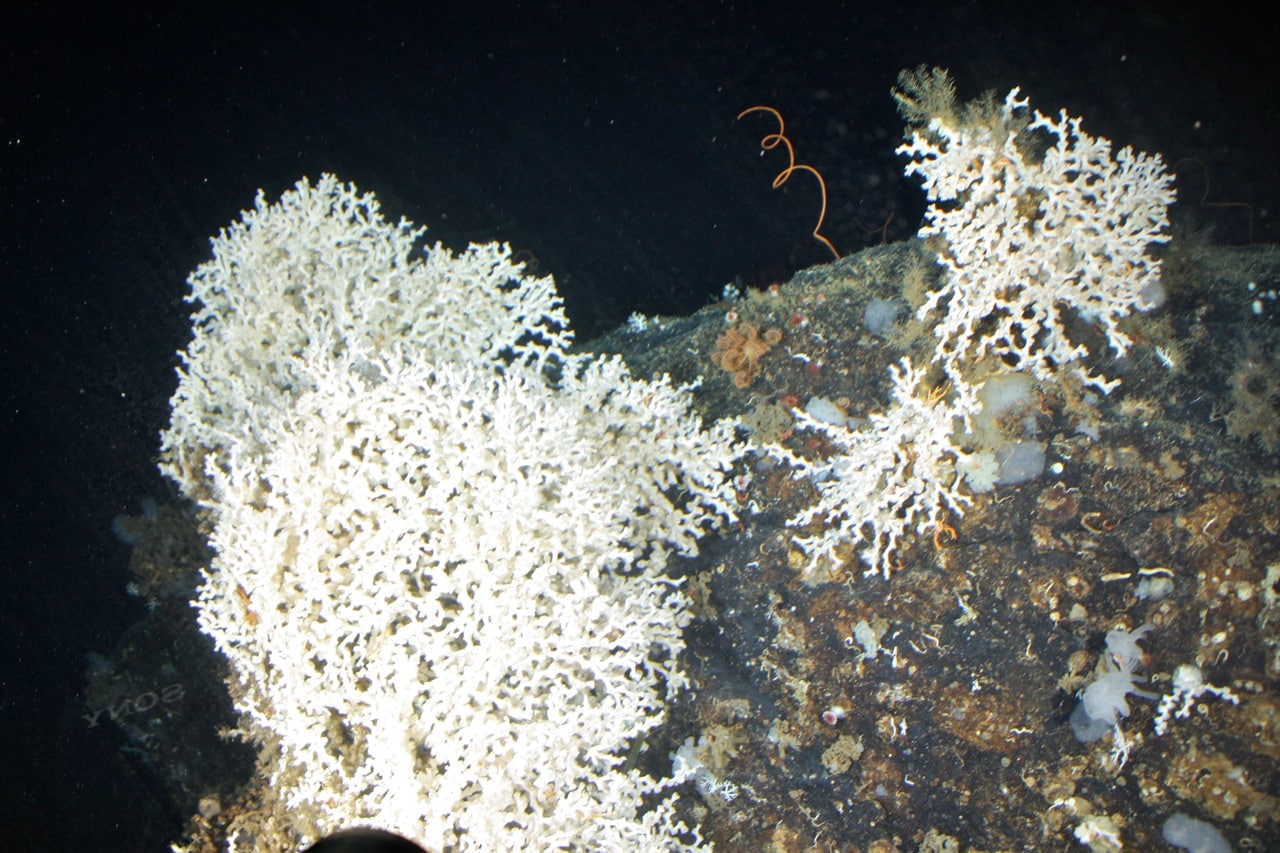

A plethora of Lophelia pertusa in Norwegian waters

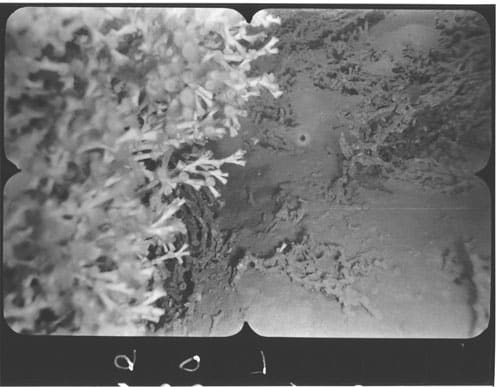

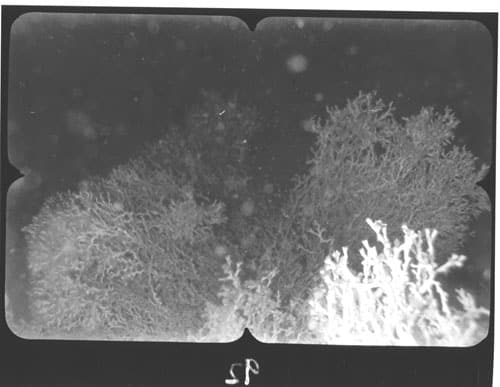

Norway has the highest known density of Lophelia pertusa reefs in the world, mapped at depths between 39 and 400 metres. The estimated spatial coverage of Norwegian Lophelia reefs is 2,000 km², a greater coverage than some countries with well known tropical reefs such as Belize, Mozambique or Seychelles. Some of these reefs have been estimated at over 8,000 years old based on geophysical, visual, geochemical, radiocarbon and other analyses. The first Lophelia reef ever photographed under water (left) in Norway was off the coast of northern Norway at 120 m water depth, in 1982, during pipeline route surveys conducted by the petroleum company Statoil. Subsequently, they were found also on the continental shelf off Mid-Norway in 1985 and onwards.

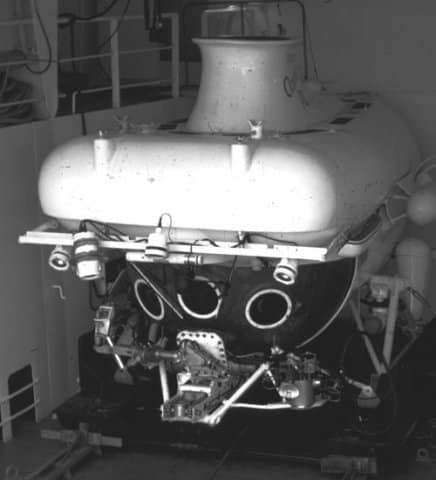

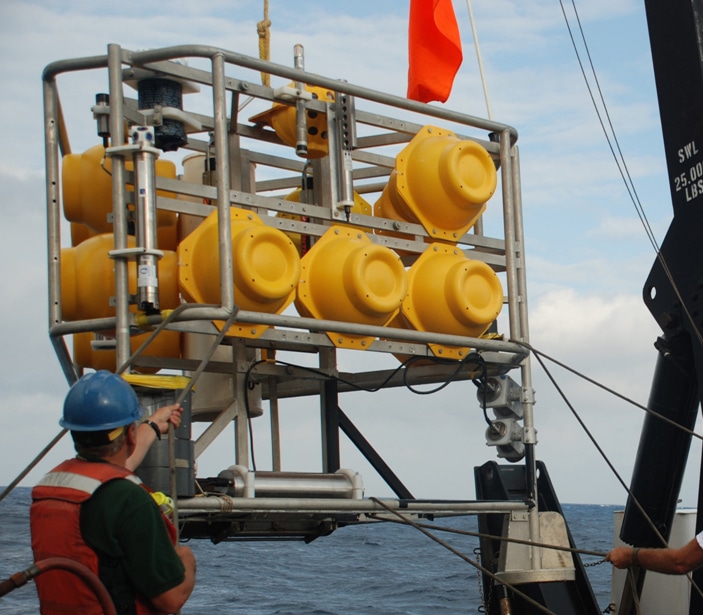

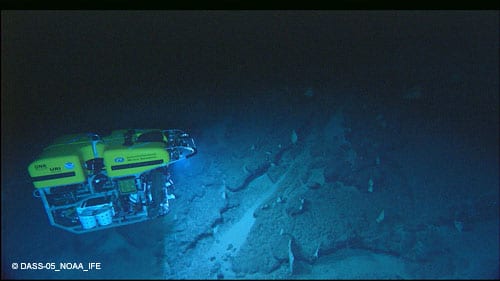

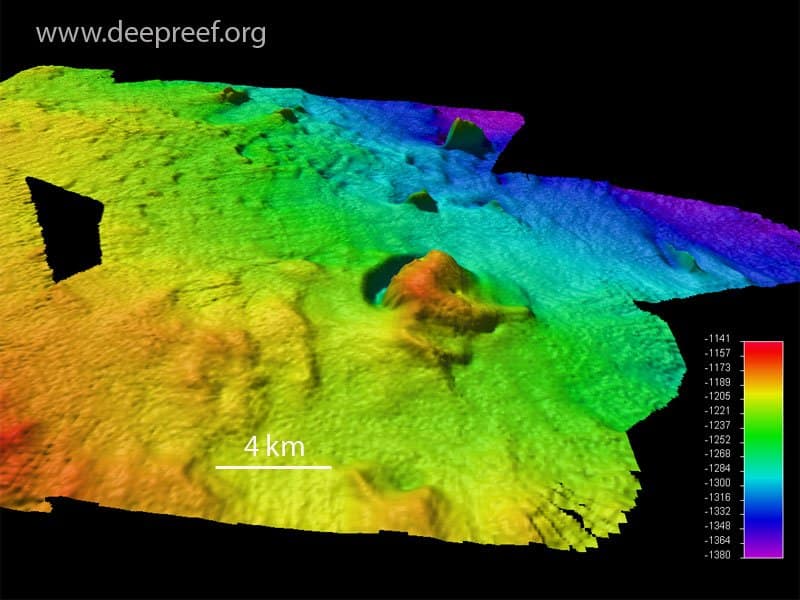

Here, acoustic surveys revealed large mounds, which were 10 to 25 m in height. It wasn’t until 1990 that the research team was able to inspect these mounds using a remotely operated vehicle – the first use of an ROV to record Lophelia reefs using colour video. Innovations also included specially designed buckets (left) to collect samples of Lophelia from the sea-floor some 280 – 300 metres down. From that point onwards research into the Norwegian Lophelia reefs has been intensive, with several hundred reefs discovered to date.

The authors thank Dr. Martin Hovland (Statoil) for contributing the amazing videos and imagery of Norwegian Lophelia reefs.

- Cairns SD (1979) The deep-water Scleractinia of the Caribbean Sea and adjacent waters. Studies on the fauna of Curaçao and other Caribbean islands 180: 1-341

- Cairns SD (1982) Stony corals (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa, Scleractinia) of Carrie Bow Cay, Belize. In: Rützler, K., Macintyre, I.G. (Eds.), The Atlantic barrier reef ecosystem at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize, I: structure and communities. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp: 271-302

- Cairns SD, Chapman RE (2001) Biogeographic affinities of the North Atlantic deep-water Scleractinia. In, Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Deep-Sea Corals (Ed. Willison JHM, Hall J, Gass SE, Kenchington ELR, Butler M, Doherty P. Ecology Action Centre, Halifax. pp: 30-57

- Etnoyer PJ, Shirley TC, Lavelle KA (2011) Deep coral and associated species Taxonomy and Ecology (DeepCAST) II Expedition Report. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 137. 42p

- Fenner D (1999) New observations on the stony coral (Scleractinia, Milleporidae, and Stylasteridae) species of Belize (Central America) and Cozumel (Mexico). Bulletin of Marine Science 64: 143-154

- Henry L-A (2011) A deep-sea coral “gateway” in the northwestern Caribbean. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 19 (6): 120–124

- Hübscher C, Dullo C, Flögel S, Titschack J, Schönfeld J (2010) Contourite drift evolution and related coral growth in the eastern Gulf of Mexico and its gateways. International Journal of Earth Sciences 99 (Supplement 1): S191-S206

- James NP, Ginsburg RN (1979) The seaward margin of Belize Barrier and Atoll Reefs. Special Publication 3, International Association of Sedimentologists, Blackwell Science, Oxford. 203pp

- Lutz S.J., Ginsberg R.N. (2007) State of deep coral ecosystems in the Caribbean region: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In: Lumsden S.E., Hourigan T.F., Bruckner A.W., Door G. (Eds.) The State of Deep Coral Ecosystems of the United States. NOAA Technical Memorandum CRCP-3, Silver Spring, MD: 307–365.

- Miloslavich P, Díaz JM, Klein E, Alvarado JJ, Díaz C, Gobin J, Escobar-Briones E, Cruz-Motta JJ, Weil E, Cortés J, Bastidas AC, Robertson R, Zapata F, Martín A, Castillo J, Kazandjian A, Ortiz M (2010) Marine biodiversity in the Caribbean: regional estimates and distribution patterns. PLoS One 5: e11916

- Reed JK, Messing CG, Walker BK, Brooke S, Correa TBS, Brouwer M (in press) Habitat characterization, distribution, and areal extent of deep-sea coral ecosystems off Florida, Southeastern U.S.A. Caribbean Journal of Science.

Videos

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 23s / 2.7 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997).

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 8s / 1 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997).

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 1m 1s / 1.6 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997).

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 1m 1s / 1.6 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997).

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 1m 6s / 1.7 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997).

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 1m 6s / 1.6 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997).

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander’.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 1m 5s / 1.7 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997)

Video footage of a large, steep, 24 m tall Lophelia reef from the Haltenpipe Reef Cluster, ‘Reef A’ (Hovland et al. 1998). Water depth 290 m. Footage taken using an ROV (‘Solo’)-mounted analogue video camera in 1997 (S-VHS-recording), with the survey vessel ‘Seaway Commander.

Location: Lat: 63° 55.4′ N, Lon: 07° 53′ E. On the continental shelf off mid-Norway (Norwegian Sea, at 300 m depth).

Running time: 1m 1s / 1.6 mb

Copyright: Statoil ASA, Norway (1997).

- Cairns SD (1979) The deep-water Scleractinia of the Caribbean Sea and adjacent waters. Studies on the fauna of Curaçao and other Caribbean islands 180: 1-341

- Cairns SD (1982) Stony corals (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa, Scleractinia) of Carrie Bow Cay, Belize. In: Rützler, K., Macintyre, I.G. (Eds.), The Atlantic barrier reef ecosystem at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize, I: structure and communities. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp: 271-302

- Cairns SD, Chapman RE (2001) Biogeographic affinities of the North Atlantic deep-water Scleractinia. In, Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Deep-Sea Corals (Ed. Willison JHM, Hall J, Gass SE, Kenchington ELR, Butler M, Doherty P. Ecology Action Centre, Halifax. pp: 30-57

- Etnoyer PJ, Shirley TC, Lavelle KA (2011) Deep coral and associated species Taxonomy and Ecology (DeepCAST) II Expedition Report. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 137. 42p

- Fenner D (1999) New observations on the stony coral (Scleractinia, Milleporidae, and Stylasteridae) species of Belize (Central America) and Cozumel (Mexico). Bulletin of Marine Science 64: 143-154

- Henry L-A (2011) A deep-sea coral “gateway” in the northwestern Caribbean. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 19 (6): 120–124

- Hübscher C, Dullo C, Flögel S, Titschack J, Schönfeld J (2010) Contourite drift evolution and related coral growth in the eastern Gulf of Mexico and its gateways. International Journal of Earth Sciences 99 (Supplement 1): S191-S206

- James NP, Ginsburg RN (1979) The seaward margin of Belize Barrier and Atoll Reefs. Special Publication 3, International Association of Sedimentologists, Blackwell Science, Oxford. 203pp

- Lutz S.J., Ginsberg R.N. (2007) State of deep coral ecosystems in the Caribbean region: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In: Lumsden S.E., Hourigan T.F., Bruckner A.W., Door G. (Eds.) The State of Deep Coral Ecosystems of the United States. NOAA Technical Memorandum CRCP-3, Silver Spring, MD: 307–365.

- Miloslavich P, Díaz JM, Klein E, Alvarado JJ, Díaz C, Gobin J, Escobar-Briones E, Cruz-Motta JJ, Weil E, Cortés J, Bastidas AC, Robertson R, Zapata F, Martín A, Castillo J, Kazandjian A, Ortiz M (2010) Marine biodiversity in the Caribbean: regional estimates and distribution patterns. PLoS One 5: e11916

- Reed JK, Messing CG, Walker BK, Brooke S, Correa TBS, Brouwer M (in press) Habitat characterization, distribution, and areal extent of deep-sea coral ecosystems off Florida, Southeastern U.S.A. Caribbean Journal of Science.

Trondheimfjord, Norway

Using the JAGO submersible onboard the FS POSEIDON

Norway is home to more Lophelia pertusa reefs than anywhere else. These reefs are found between 40 and 400 m and cover around 2,000 km² – more than some countries with well known tropical reefs including Belize, Mozambique or the Seychelles. Some of these reefs have been dated at over 8,000 years old.

The reefs in Trondheimsfjord are relatively sheltered compared to those found outside the fjords so they often provide ideal conditions for submersible or ROV dives. These reefs can exist within the fjords, as incoming seawater from the Norwegian Sea is denser than freshwater runoff from the land so conditions are suitable for corals to grow even far from the open sea. In September 2011, a research expedition onboard the FS POSEIDON sailed from Kiel, Germany, to the Trondheimsfjord Reefs in Norway. This expedition was a collaboration between researchers from Germany, the UK and the Netherlands working together to study the impacts of ocean acidification on cold-water coral ecosystems and to assess the biodiversity of life on Trondheimsfjord reefs. The JAGO two-man submersible was used to record and photograph areas on the reef and to collect samples to return them to holding tanks onboard the POSEIDON. Following a dive, biodiversity samples are sorted out on deck before being moved to suitable holding facilities for further identification.

You can see examples of the different environments and organisms on our image page.

Experimental work

Characterising cold water coral metabolism

Unlike tropical coral species, very little is known about the baseline metabolism and biology of cold water coral species such as Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata. Until now, the acclimation of these species across environmental gradients has not been considered, but with JAGO’s ability to collect precise colonies from across the reef, scientists onboard the POSEIDON conducted comparative experiments on Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata from a variety of habitats. Experiments were designed to contrast and compare metabolism, carbon budgets and calcification rates of Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata from numerous locations.

You can see examples of how the different environments such as exposed and sheltered areas on a reef look like in our video below.

Video

The JAGO two-man submersible recorded this video of the Trondheimsfjord Reefs in September 2011. Copyright GEOMAR and Lophelia.org

- Fosså JH, Mortensen PB, Furevik DM (2000) Lophelia-korallrev langs norskekysten forekomst og tilsand. Fisken og Havet 2: 1-94

- Fosså JH., Mortensen PB, Furevik DM (2002) The deep-water coral Lophelia pertusa in Norwegian waters: Distribution and fishery impacts. Hydrobiologia 471: 1-12

- Fosså JH, Alvsvåg J (2003) Kartlegging og overvåkning av korallev. In: Havets Miljø 2003 (eds Asplin L, Dahl E). Fisken og Havet. Special Issue 2-2003: 62-67

- Freiwald A, Henrick R, Pätzold J (1997) Anatomy of a deep-water coral reef mound from Stjernsund, West-Finnmark, Northern Norway. SEPM, Special Publication 56: 141-161

- Freiwald A, Huhnerbach V, Lindberg B, Wilson JB, Campbell J (2002) The Sula Reef Complex, Norwegian shelf. Facies 47: 179-200

- Hovland M, Risk M (2003) Do Norwegian deep-water coral reefs rely on seeping fluids? Marine Geology 198: 83-96

- Hovland M, Vasshus S, Indreeide A, Austdal L, Nilsen O (2002) Mapping and imaging deep-sea coral reefs off Norway, 1982-2000. Hydrobiologia 471 :13-17

- Mortensen PB, Hovland MT, Fosså JH, Furevik DM (2001) Distribution, abundance and size of Lophelia pertusa coral reefs in mid-Norway in relation to seabed characteristics. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 81: 581-597

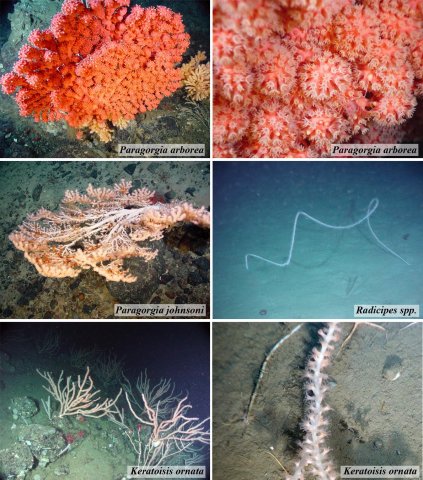

Canadian Atlantic

The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), university, NGO and industry scientists began collecting information on the cold-water corals from waters off Atlantic Canada in the 1990s. Today, over 30 coral species have been identified from this region, including the framework-forming scleractinian Lophelia pertusa. The most distinguishing feature fauna of this region are the dense stands of soft corals such as Paragorgia arborea, Primnoa resedaeformis, Paramuricea grandis and Keratoisis ornata and of sea pens such as Pennatula borealis. Some of the largest concentrations of sea pens reported thus far are found in the Laurentian Channel.

Corals are particularly abundant in deep basins and gullies in waters off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland including the Gully, the Northeast Channel, Laurentian Channel and off the Grand Banks. A Government of Canada Technical Report was recently published describing the distribution of corals in the Maritime Provinces, particularily in regards to conservation areas (Northeast Channel Coral Conservation Area, The Gully Marine Protected Area, and the Stone Fence Lophelia Conservation Area). In 2010, a comprehensive assessment of coral and sponge distribution in eastern Canada from Davis Strait in the north to Georges Bank in the south was published using data collected from the ecosystem or multispecies trawl surveys within Canada’s exclusive economic zone. Maps in these and other reports (including ICES Working Group on Deepwater Ecology -WGDEC) were produced using data held in a MS Access database referred to as the Matitimes Region Coral and Sponge Repository. This database is continually updated as new information becomes available.

We thank Dr. Ellen Kenchington and Mr. Andrew Cogswell at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Department of Fisheries & Oceans Canada for text and images

Current status

The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), in collaboration with university, NGO and industry partners, began collecting information on the cold-water corals from waters off Atlantic Canada in 1997, alongside local knowledge provided by fishing communities going back centuries. Many coral species were identified from these waters, including the framework-forming scleractinians Lophelia pertusa and solitary species such as Flabellum spp. and Desmophyllum dianthus. But perhaps the most distinguishing feature fauna of this region are the lush communities of soft corals such as the gorgonians Paragorgia arborea, Primnoa resedaeformis, Paramuricea grandis and long-lived bamboo corals such as Keratoisis ornata. Atlantic cold-water corals are particularly abundant and rich in deep basins and gullies off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland including the Gully, the Northeast Channel, Laurentian Channel and off the Grand Banks. Similar to the Lophelia pertusa carbonate mounds of the bathyal NE Atlantic, cold-water corals in the NW Atlantic are often associated with hard substrata created by glacial deposits and erosional unconformities. A video link provided by DFO can be viewed here to fully appreciate these habitats in Atlantic Canada .

Beginning in 2003, alongside other government departments, the fishing industry, and other oceans-related stakeholder interest groups, DFO began drafting a “Coral Conservation Plan” for the Maritime Region (Canadian EEZ waters off New Brunswick and Nova Scotia) to document research activities and to direct conservation, management, and future study. The Plan was completed in 2006 and identified areas of the highest priority for research and management. Currently there are conservation measures for several areas in the Maritimes DFO jurisdiction: a coral conservation zone in the Northeast Channel (SW Nova Scotia), with 90% of the 424 km2 area closed to all forms of bottom fishing; a 15 km2 Lophelia coral conservation zone located in the Stone Fence area of the Laurentian Channel; and the Gully MPA, a 2364 km2 area inhabited by rich communities and diverse habitat types, with restricted (but not prohibited) human activities. Although no marine protected areas are currently in place for corals living off Newfoundland and Labrador, conservation measures are in place to protect the larger habitat-forming gorgonian “forests” and the regional fishing community has proposed a voluntary closure off the Hudson Strait.

Links

- Campbell JS, Simms JM (2009) Status Report on Coral and Sponge Conservation in Canada. Fisheries and Oceans Canada: vii + 87 p

- Cogswell AT, Kenchington ELR, Lirette CG, MacIsaac K, Best MM, Beazley LI, Vickers J (2009) The current state of knowledge concerning the distribution of coral in the Maritime Provinces. Canadian Technical Report on Fisheries and Aquatic Science 2855: v + 66 p.

- ESSIM Planning Office (2006) Coral conservation plan. Maritimes Region (2006-2010). Oceans and Coastal Management Report 2006-01. 71p

- FAO: International Guidelines for the Management of Deep-sea Fisheries in the High Seas. Rome, FAO. 2009. 73 p

- Gass SE, Willison JHM (2005) An assessment of the distribution of deep-sea corals in Atlantic Canada by using both scientific and local forms of knowledge. In: Freiwald A, Roberts JM (Eds) Cold-water corals and ecosystems. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg pp 223-245

- Gilkinson K, Edinger E (2009) The ecology of deep-sea corals of Newfoundland and Labrador waters: biogeography, life history, biogeochemistry, and relation to fishes. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2830: vi + 136p

- Kenchington E, Lirette C, Cogswell A, Archambault D, Archambault P, Benoit H, Bernier D, Brodie B, Fuller S, Gilkinson K, Levesque M, Power D, Siferd T, Treble M, Wareham V (2010) Delineating Coral and Sponge Concentrations in the Biogeographic Regions of the East Coast of Canada Using Spatial Analyses. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2010/041: vi + 202 pp.

- Kenchington E, Cogswell A, Lirette C, Rice J (2010) A geographic information system (GIS) Simulation Model for Estimating Commercial Sponge By-catch and Evaluating the Impact of Management Decisions: DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2010/040. vi + 40 p.

- Kenchington E, Best M, Cogswell A, MacIsaac K, Murillo-Perez FJ, MacDonald B, Wareham V, Fuller SD, Jørgensbye HIØ, Sklya V, Thompson AB (2009). Coral Identification Guide NAFO Area.

- Kenchington E, Cogswell A, Lirette C, Muillo-Prez FJ (2009) The Use of Density Analyses to Delineate Sponge Grounds and Other Benthic VMEs from Trawl Survey Data. NAFO SCR. Doc. 09/6

- Murillo FJ, Durán Muñoz P, Altuna A, Serrano A (2010) Distribution of deep-water corals of the Flemish Cap, Flemish Pass, and the Grand Banks of Newfoundland (Northwest Atlantic Ocean): interaction with fishing activities. ICES Journal of Marine Science doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsq071

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 61/105

UK

Current status

The UK’s EEZ supports a diverse range of marine habitats, including many that are inhabited by cold-water corals. Lophelia pertusa is found on the Wyville Thomson Ridge, across Rockall, in the Sea of the Hebrides and on the Darwin Mounds, in addition to many species of octocorals, black corals and stylasterid hydrocorals. Lophelia inhabits many of the UK’s marine habitats, including the inshore continental shelf, offshore slopes and seamounts, and sandy mounds. Inshore, off the island of Mingulay (western Scotland, approximately 130 – 200 m deep) and offshore Rockall (Hatton Bank, approximately 400 – 1000 m deep), Lophelia builds large, biogenic reef-topped mounds that support highly diverse benthic communities.

Although the spatial extent of different human activities varies, it is clear that bottom fishing in UK waters has the most devastating widespread effect on cold-water corals. Many marine habitats colonised by Lophelia and other corals in UK waters now enjoy various degrees of public awareness and protection. In offshore waters the Darwin Mounds, Wyville Thomson Ridge and North West Rockall Bank are all candidate SACs, while in territorial waters the Mingulay Reef Complex was approved by Scottish Ministers as a Special Area of Conservation in August 2011. Damaging fishing activity is currently prohibited at the Darwin Mounds by a measure under the Common Fisheries Policy.

Currently, no national legislation exists protecting Lophelia pertusa reefs or cold-water corals in general, although they do feature in the non-statutory UK Biodiversity Action Plan, which recommends conservation actions including research on their distribution in UK waters and designation of marine protected areas. Recent activities such as the Strategic Environmental Assessment initiative will generate new information based on new multibeam sonar surveys and photographic surveys, which may be used in conservation efforts.

Pisces and Rockall Bank

Pioneering dives of discovery

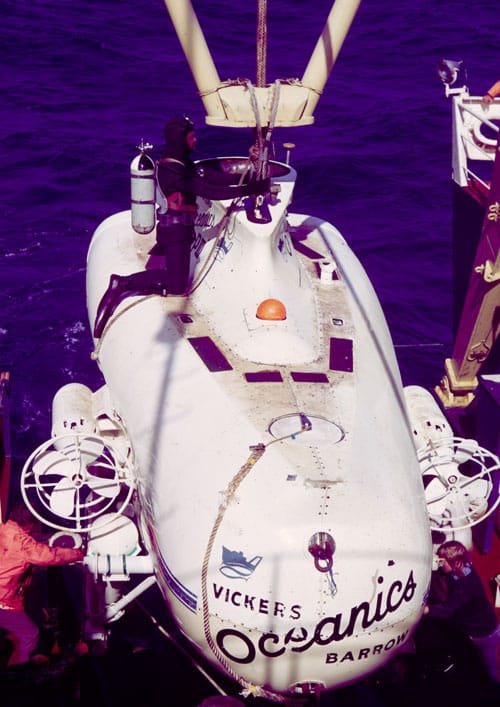

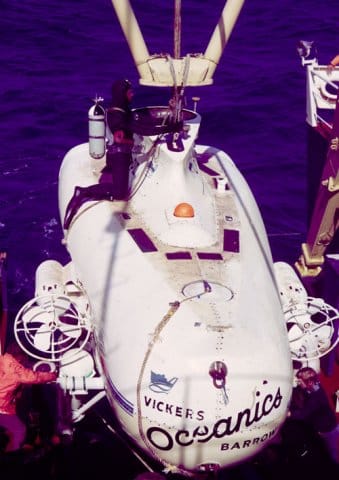

In June 1973, Dr. John Wilson and pilot George Colquhoun dived in the Pisces III submersible in search of Lophelia on Rockall Bank. These pioneering dives took video and still images of Lophelia reefs on the Rockall Bank 350 miles offshore and were used by John Wilson in his classic descriptions of Lophelia coral growth and patch development published in 1979.

The video tapes and original recorders were stored for thirty years and thanks to the video restoration experts and engineers at the British Film Institute they have been carefully restored and transferred to modern digital formats.

Watch clips from the Pisces III restored video below.

The authors thank Dr. John Wilson for the images and video shown in this section.

Video

Compilation of the restored Pisces III dive made by John Wilson and George Colquhoun at Rockall Bank in 1973. Large thickets of Lophelia corals are observed and other amazing underwater life. This video was restored by experts at the British Film Institute working in collaboration with Murray Roberts of Heriot-Watt University (Includes sound-track of commentary from 1973).

Location: Lat: 57° 36′ 42.44″ N, Lon: 14° 29′ 6.96″ W. Rockall Bank (north-east Atlantic, at 250 m depth).

Running time: 10 m 13 s / 21.3 mb.

Video Editing: A.J. Davies & J.M. Roberts (2006).

- Roberts DG, Eden RA et al. (1974) DE “Vickers Voyager” and “Pisces III” June – July 1973. Submersible investigations of the geology and benthos of the Rockall Bank. Wormley, UK, Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, 22pp. (Institute of Oceanographic Sciences Cruise Report, 1)

- Wilson JB (1979) The distribution of the coral Lophelia pertusa (L.) [L. prolifera (Pallas)] in the North-East Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 59:149-164.

- Wilson JB (1979) ‘Patch’ development of the deep-water coral Lophelia pertusa (L.) on Rockall Bank. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 59:165-177

- van Oevelen et al. (2009) The cold-water coral community as hotspot of carbon cycling on continental margins: A food-web analysis from Rockall Bank (northeast Atlantic). Limnology and Oceanography 54 (6): 1829-1844

- Dorschel B, Wheeler AJ, Huvenne VAI (2009) Cold-water coral mounds in an erosive environmental setting: TOBI side-scan sonar data and ROV video footage from the northwest Porcupine Bank, NE Atlantic. Marine Geology 264(3-4): 218-229

- Dullo WC, Flogel S, Ruggeberg A (2008) Cold-water coral growth in relation to the hydrography of the Celtic and Nordic European continental margin. Marine Ecology Progress Series 371:165-176

Mingulay Reef Complex

Scotland’s only known inshore coral reef

Coral reefs and Scotland might not seem to go together, but in fact a large coral reef has been growing just 13 km from the Island of Mingulay for at least the last 5000 years. The reefs were only discovered in 2003 when the area was mapped using modern mapping sonar techniques. The new surveys revealed several reefs of Lophelia pertusa corals forming what is now known as the Mingulay Reef Complex. Before then corals in this area had been occasionally caught by fishermen and recorded by Victorian naturalists. The only person to report live Lophelia in the area was John Wilson who saw a few scattered colonies from the Pisces II submersible in 1970.

The modern sonar surveys gave a glimpse of a hidden world but threw up many questions. Were these the only coral reefs in the area? Why are the corals growing here in particular? What are they feeding on? How old are the reefs?

Since 2003 the Mingulay Reef Complex has become one of the most intensively studied cold-water coral reefs in the world. Researchers from around Europe have teamed up to work out why the reefs are growing there and to study their biodiversity. Follow the links on the left or Go Deeper to discover more.

Current status

From the early 19th century, most records of Lophelia pertusa from the west coast of Scotland came from fishermen and naturalists. It was not until the late 1960s and early 1970s that scientists discovered L. pertusa once again. Research began again in the late 1990s, and the area was surveyed and mapped in 2003, when the true extent of the reefs was first uncovered, see our Mingulay Reefs Case Study.

Many areas of the reef complex have now been mapped in detail; its rich biodiversity is being uncovered, its hydrography, while complex, provides the baseline for explaining the occurrence and biodiversity of its associated fauna, studies of the palaeoecology and oceanography are underway, trophic studies have revealed the life habits of L. pertusa, and several new species have been discovered.

A consultation over future conservation measures was begun in November 2010 and concluded with approval from Scottish Ministers to create a Special Area of Conservation in August 2011. The SAC proposal will now be submitted to the European Commission for inclusion in the European Union-wide ‘Natura’ network of protected areas.

Mapping Mingulay

Multibeam echosounders to map a reef

The reefs at Mingulay were discovered using a multibeam echosounder secured to the hull of the RV Lough Foyle in the summer of 2003 (see Mapping and View Location in Google Earth for images). By carefully going through historic coral records back to the mid-eighteenth century and using the available charts of the seafloor, researchers selected areas of the seabed with steep slopes where exposed rocks or piles of stones dropped by retreating icebergs thousands of years ago may have provided a perch for corals to settle and grow.

With limited time and money, the 2003 surveys had to focus in just a few areas and produced a series of multibeam maps showing not just the shape of the seafloor, but also something about its texture from strength of the acoustic return (the so-called ‘backscatter’).

The first area surveyed, till this day known as Mingulay Area 1, was immediately exciting – there were many lumps and bumps concentrated in one particular area and extending along a ridge that cut right across the seabed. As soon as video cameras were lowered onto this area it was clear that these lumps and bumps were in fact a whole series of Lophelia coral reefs, some growing more than 5 m above the surrounding seafloor (see Coral Reef Mounds Location for images). But why were there corals here and not in other areas? Why were they growing on the flanks of this large seabed ridge?

Figuring this out meant understanding the water flows – known as the hydrography – of the area.

Hydrography

Why are there cold-water coral reefs at Mingulay?

The answer to this question took the joint efforts of scientists from several countries working together through the European HERMES project. Although shallow by deep-sea coral standards, the reefs at Mingulay are still too deep to study by diving and too remote for daily visits by a research ship. So how do you build up a picture of life in the Mingulay Reef Complex?

The answer is by using deep-sea landers that sit within the corals for up to a year recording information about their environment. The landers used at Mingulay were built by the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) who brought their research ship RV Pelagia to Mingulay in 2006 and 2007. The landers were equipped with current meters and optical sensors and set down carefully amongst the coral reefs.

The current meters on the landers gave researchers the first idea of the world experienced by Lophelia in its natural habitat within the Mingulay reefs. Even at depths of over 100 m, the corals still feel the effects of the tide. At Mingulay Area 1, the first area mapped in 2003, there was a strong pattern related to these tides. Every six hours the corals are washed by warmer water coming down from the surface. As well as being warmer, the water contained more plant plankton (or phytoplankton) – this was detected by the optical sensors because the pigments in the phytoplankton fluoresce.

By working with specialists in the physics of water flow, the researchers worked out that the corals were growing on the flanks of the large rocky ridge because the ridge interrupted the wave-like flow, creating turbulence and causing foods-rich surface waters to wash down across the seabed. Time and tide wait for no man, and every six hours the corals at Mingulay can expect a dose of warm, food-rich water.

Biodiversity

350 species and counting…

Like other Lophelia reefs, those at Mingulay are home to many other animals. The reefs form a city beneath the sea with vertical coral walls extending upwards for several metres to large white expanses of live coral exposed to the full force of water currents. Between the reefs are hollows and crevices sheltered from the water currents where other animals can live in the sands and mud trapped in the dead coral branches.

All these different habitats provide a huge variety of niches for other species. Like the Lophelia corals themselves, animals that catch their prey from the water currents tend to perch high up in the reef structures or in areas between reefs where the turbulent waters are slowed.

Over the last seven years researchers have begun to build up a picture of the biodiversity at Mingulay. So far over 350 different animals have been recorded including 100 species of sponges alone. Among the sponges was a previously unknown species that lives by boring into the dead coral skeletons. In honour of its Scottish origins, this was named Cliona caledoniae by Rob van Soest and Elly Beglinger from the University of Amsterdam.

You can see examples of some of the animals living on the Mingulay reefs on our video page.

Video

Footage from ROV dives on the cold-water corals of the Mingulay Reef Complex.

Running time: 5.35

- Davies AJ, Duineveld G, Lavaleye M, Bergman M, van Haren H, Roberts JM (2009) Downwelling and deep-water bottom currents as food supply mechanisms to the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia) at the Mingulay Reef Complex. Limnology & Oceanography 54: 620-629

- Dodds LA, Black KD, Orr H, Roberts JM (2009) Lipid biomarkers reveal geographical differences in food supply to the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia). Marine Ecology Progress Series 397: 113-124

- Dodds LA, Roberts JM, Taylor AC, Marubini F (2007) Metabolic tolerance of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia) to temperature and dissolved oxygen change. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 349: 205-214

- Eden RA, Ardus DA, Binns PE, McQuillin R, Wilson JB (1971) Geological investigations with a manned submersible off the west coast of Scotland 1969-1970. Report No. 71/16, Institute of Geological Sciences, London

- Fleming J (1846) On the recent Scottish Madrepores, with remarks on the climatic character of the extinct races. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 2: 82-83

- Gosse PH (1860) Actinologica Britannica. A History of the British Sea-Anemones and Corals. xi, Van Voorst, London, 362pp

- Long D, Roberts JM, Gillespie EJ (1999) Occurrences of Lophelia pertusa on the Atlantic margin. British Geological Survey Report WB/99/24, Edinburgh, 23pp

- Henry L-A, Davies AJ, Roberts JM (2010) Beta diversity of cold-water coral reef communities off western Scotland. Coral Reefs 29: 427-436

- Roberts JM, Brown CJ, Long D, Bates CR (2005) Acoustic mapping using a multibeam echosounder reveals cold-water coral reefs and surrounding habitats. Coral Reefs 24: 654-669

- Roberts JM, Davies AJ, Henry L-A, Duineveld GCA, Lavaleye MSS, Dodds LA, Maier C, van Soest RWM, Bergman MIN, Hühnerbach V, Huvenne V, Sinclair D, Watmough T, Long D, Green S, van Haren H (2009) Mingulay reef complex: an interdisciplinary study of cold-water coral habitat, hydrography and biodiversity. Marine Ecology Progress Series 397: 139-151

- Roberts JM, Long D, Wilson JB, Gage JD (2003) The cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia) and enigmatic seabed mounds along the northeast Atlantic margin: are they related? Marine Pollution Bulletin 46:7-20

- Wilson JB (1979a) The distribution of the coral Lophelia pertusa (L.) [L. prolifera (Pallas)] in the northeast Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK 59: 149-162

- Wilson JB (1979b) The first recorded specimens of the deep-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Linnaeus 1758) from British waters. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology Series 36: 209-215

Rockall-Hatton Bank

Current status

In 2007, the Northeast Atlantic Fisheries Management Commission (NEAFC) announced a prohibition on bottom fishing in several coral-inhabited areas around the Rockall-Hatton Bank area, which have been identified as vulnerable marine ecosystems (VMEs).

In 2010, all bottom gear including trawling and the use of static gear such as set gillnets and longlines were prohibited in NW and SW Rockall as well as areas on Hatton Bank. In September 2010, the Convention for the Protection and of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR) announced a network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) that are now in place, two of which include areas inhabited by cold-water corals within UK jurisdiction. In addition to the Darwin Mounds MPA, both the WyvilleThomson Ridge and the NW Rockall Bank became candidate SACs, following the Joint Nature Conservation Commitee’s (JNCC) submissions to criteria outlined by the Habitats Directive.

Darwin Mounds

Current status

The Darwin Mounds, which contain patch reefs of Lophelia pertusa, were discovered by the scientific community in 1998. Evidence for significant trawling damage in the region of these rather unique coral reefs (L. pertusa inhabiting mobile sandy substrata instead of the more typical hard rocky substrata), and in 2004, was designated the first UK marine protected area (MPA), covering approximately 1380 km² of surrounding seabed. Partnerships between Greenpeace, oil and gas industry and UK governmental bodies such as the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Scottish Executive were instrumental in the discovery and progression of the Darwin Mounds to MPA status.

South Eastern USA

Most extensive cold-water coral areas in the US

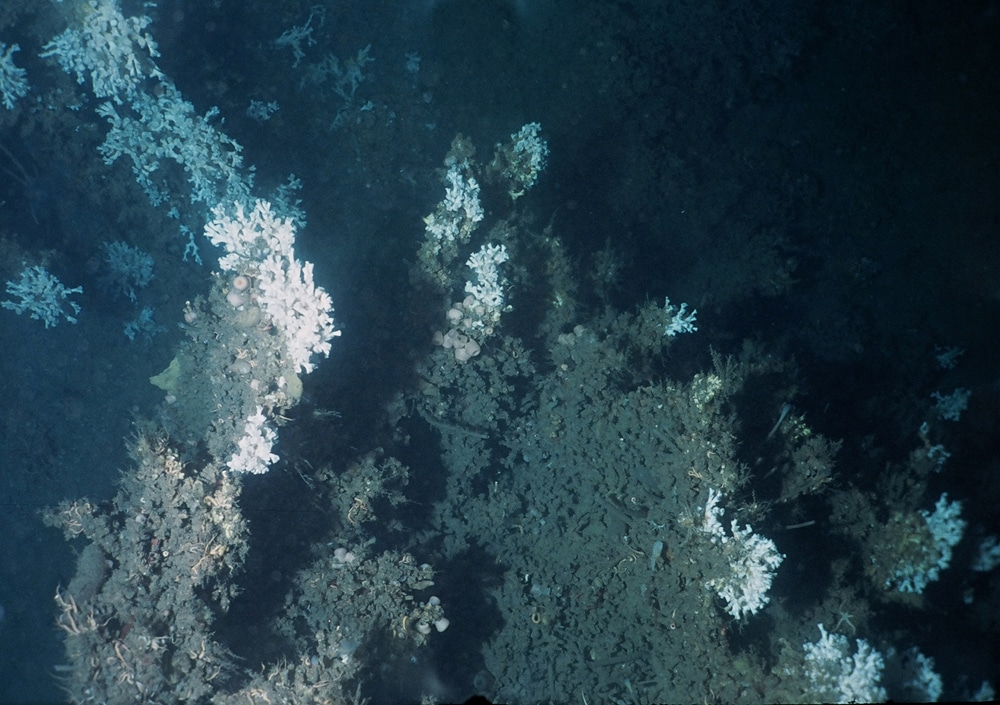

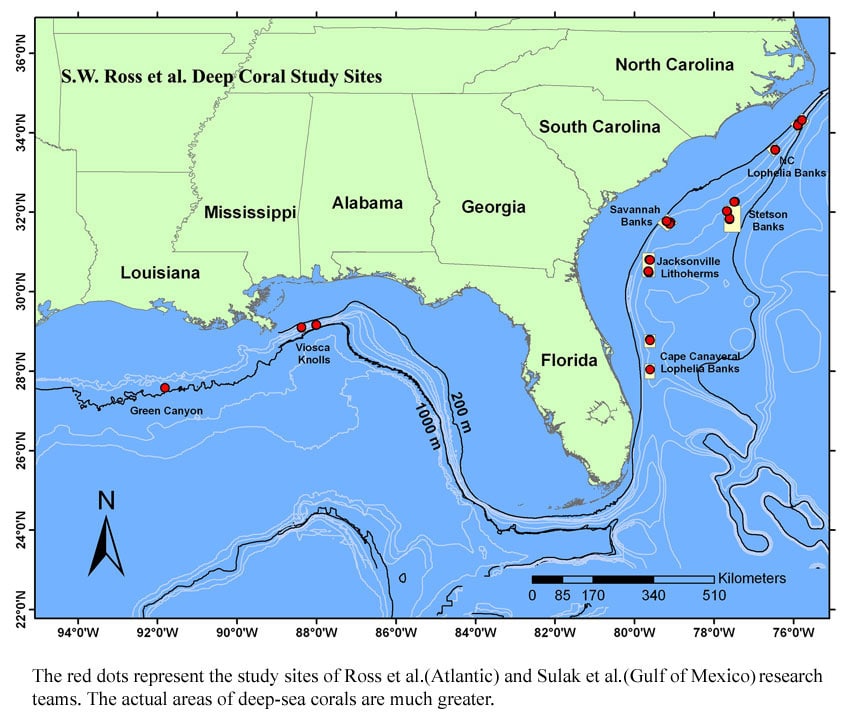

Off the south eastern United States (SEUS) coast there are extensive and productive cold-water coral habitats. These extend from Cape Lookout, North Carolina through the Straits of Florida and include scattered locations in the Gulf of Mexico over a range of depths from about 360 m to at least 1000 m. By one estimate, the SEUS and Gulf of Mexico have the most extensive cold-water coral areas in the US. These areas have been poorly studied, partly due to their depths, rugged bottom topography and the fact that they are usually overlain by extreme currents (i.e. the Gulf Stream).

Cold-water corals (> 200 m) in the SEUS are diverse with at least 47 species of solitary, ahermatypic hard corals, 10 species of colonial (some hermatypic) hard corals, and 52 species of soft and horny corals. Conservatively, the region contains at least 109 species of cold-water corals (classes Hydrozoa and Anthozoa). Most of these species are either solitary or do not form major reef structures, but they all contribute to habitat complexity. As in other parts of the world, Lophelia pertusa, is the major reef-building coral in the region, and it is common on appropriate substrates throughout the SEUS in depths of about 370m to at least 800 m. Off North Carolina, Lophelia forms what may be considered classic mounds that appear to be a sediment/coral rubble matrix topped with almost monotypic stands of Lophelia. To the south, sediment/coral mounds are smaller and scattered; however, Lophelia and other hard and soft corals populate the abundant hard substrates of the Blake Plateau in great numbers. Other scleractinians, such as the colonial corals Madrepora oculata and Enallopsammia spp., contribute to the overall complexity of the habitat. Species diversity of scleractinians appears to increase south of Cape Fear, North Carolina. Bamboo and black corals are also important structure-forming corals (reaching heights of 1-2 m) in the SEUS. They occur locally in moderate abundances, generally south of Cape Fear, NC.

The authors thank Dr. Steve W. Ross (UNC-W) for contributing the text, videos and imagery of the South Eastern USA Lophelia reefs.

Current status (general USA)

The waters surrounding the USA contain a wide variety of different coral species, including both tropical and cold-water corals. The cold-water corals are usually found along the continental shelf and in canyons. So far, several species of octocoral have been found to be common, and over 17 species of stony corals have been found.

Scientists first discovered a major cold-water reef complex consisting of Oculina varicosa, along the continental shelf edge about 26 to 50 km off Florida’s central east coast. Since the discovery of these Oculina banks in 1975 it appears that the condition of these reefs and the fish productivity has declined.

This resulted in the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council designating the area an MPA. Since 1984 a total of 315 km² has been protected, with trawling, dredging and anchoring banned. In 1994, hook and line fishing was banned for ten years and has since been extended indefinitely. The MPA has been extended to cover 1029 km² since 2000, but there is still evidence that illegal trawling is taking place. In 2004, a further six areas were put forward as potential Habitat Area of Particular Concern and may receive protected status in the future.

The Aleutian Islands are located in US territorial waters off the coast of Alaska and are under immense fishing pressure. The waters surrounding these Islands are heavily fished, with commercial species such as walleye Pollock, Pacific Code, Atka mackerel, rock fish and sablefish all valuable catches. US fisheries observers recorded approximately 2 million kg of coral and sponge bycatch between 1990 and 2002.

In 2005, the US fisheries body, NOAA Fisheries, announced the creation of the Aleutian Islands Habitat Conservation Area, an area exceeding 274,000 square nautical miles. This area is closed to bottom trawling fisheries and also contains other conservation measures protecting essential fish habitat in Alaska. In the Gulf of Alaska, ten habitat conservation habitat areas have been closed to bottom trawling and five smaller areas in south-east Alaska will be closed to all bottom contact fishing to protect coral habitat. Additionally, 15 areas surrounding seamounts will be closed to bottom contact fishing.

| Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, Alaska Fisheries, NOAA, USA |

Videos

Beneath the Blue: An award winning cold-water coral film by ARTWORK Inc. for the South Atlantic Fisheries Management Council. Developed in conjunction with the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh and the UNCW Center for Marine Science.

Running time: 19m 57s / 18mb (WMV)· (QT).

Copyright: ARTWORK Inc (2008).

Collecting Samples of Lophelia

Running time: 1m 32s / 2.3 mb

Copyright: S.W. Ross et al, UNC-W, NOAA-OCE (2005)

A bringisid amongst the corals

Running time: 32s / 0.8 mb

Copyright: S.W. Ross et al, UNC-W, NOAA-OCE (2005)

A spider crab and anemones on the corals

Running time: 1m 06s / 1.7 mb

Copyright: S.W. Ross et al, UNC-W, NOAA-OCE (2005)

- Genin A, Paull CJ, Dillon WP (1992) Anomalous abundances of deep-sea fauna on a rocky bottom exposed to strong currents. Deep-sea Research 39: 293-302

- Hain S, Corcoran E (2004) 3. The status of the cold-water coral reefs of the world. In: Wilkinson, C (Ed.) Status of coral reefs of the world: 2004. Vol 1. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Perth, Western Australia. p 115-135

- Messing CG, Neumann AC, Lang JC (1990) Biozonation of deep-water lithoherms and associated hardgrounds in the northeastern Straits of Florida. Palaios 5: 15-33

- Neumann AC, Ball MM (1970) Submersible observations in the Straits of Florida: geology and bottom currents. Geological Society of America – Bulletin 81: 2861-2874

- Neumann AC, Kofoed JW, Keller G (1977) Lithoherms in the Straits of Florida. Geology 5: 4–10

- Paull CK, Neumann AC, am Ende BA, Ussler III W, Rodriguez, NM (2000) Lithoherms on the Florida-Hatteras slope. Marine Geology 166: 83-101

- Reed JK (2002) Comparison of deep-water coral reefs and lithoherms off southeastern USA. Hydrobiologia 471: 57-69.

- Reed JK, Ross SW ( 2005) Deep-water reefs off the southeastern US: recent discoveries and research. Current 21(4): 33-37

- Squires DF (1959) Deep sea corals collected by the Lamont Geological Observatory. I. Atlantic corals. American Museum Novitates 1965: 1-42

- Stetson TR, Squires DF, Pratt RM (1962) Coral banks occurring in deep water on the Blake Plateau. American Museum Novitates 2114: 1-39

Ireland

Current status

Current status

The Porcupine Seabight, with its banks of coral reefs and carbonate mounds is found off the west coast of Ireland. After researchers uncovered that there may be significant damage being caused to these areas, the Irish Government established a group of representatives from government departments and government agencies, industry, academia and the legal profession in 2001. The group was set up to advise policy makers on the need to conserve cold-water corals.

In June 2003, the Irish Government announced its intention to designate a number of offshore sites as cold-water coral Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) under the EU Habitats Directive. The Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government is currently engaged in identifying suitable sites. Formal designation of SACs will take place after a period of consultation.

- Grehan A, Unnithan V, Wheeler A, Monteys X, Beck T, Wilson M, Guinan J, Foubert A, Klages M, Thiede J (2004) Evidence of major fisheries impact on cold-water corals in the deep waters off the Porcupine Bank, west coast of Ireland: are interim management measures required? Proceedings ICES Annual Science Conference 22-25 September, Vigo, Spain.

- Hall-Spencer JM, Allain V, Fossa JH (2002) Trawling damage to Northeast Atlantic ancient coral reefs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 269: 507-511

- Wheeler A, Beck T, Thiede J et al (2005) Deep-water coral mounds on the Porcupine Bank, Irish Margin: preliminary results from the Polarstern ARK-XIX/3a ROV cruise. In : Freiwald A, Roberts JM (eds) Cold-Water Corals and Ecosystems. Springer, New York

- Wattage P, Glenn H, Mardle S et al (2010) Economic value of conserving deep-sea corals in Irish waters: A choice experiment study on marine protected areas. Fisheries Research doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2010.10.007

Gulf of Mexico

Scattered colonies on carbonate blocks

Records of cold-water corals in the Gulf of Mexico (GoM) date back to surveys conducted by Pourtalès in the Straits of Florida and between the Dry Torugas and the Campeche Bank in the 19th century. In the deeper areas of the GoM, the substrata are mostly composed of fine sediments. However, unlike many cold-water coral habitats, much of the hard substrata colonised by corals are formed from authigenic carbonate (Go Deeper). These large carbonate blocks are deposited by biogeochemical activity that is associated with the seepage of hydrocarbons, a common feature of the GoM.

While there are substantial areas of cold-water coral habitat in the GoM, it appears to be more scattered and less extensive than such habitats off the southeastern US. Much of the research into the cold-water coral communities of the GoM has taken place along the northern continental slope. Here, several studies have found coral habitat consisting of reef building species such as Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata. The most extensive cold-water coral communities found to date in the Gulf of Mexico occur at the Viosca Knoll, located on the upper DeSoto Slope, about 65 nautical miles south of the mouth of Mobile Bay, Alabama. The main Viosca Knoll site (called VK826) is an isolated feature that rises 90 m from the surrounding seafloor, providing high relief for an array of suspension feeders including scleractinian, gorgonian and anthipatharian corals.

Viosca Knoll was an important site for a 2008-2009 international collaboration between American, Dutch and Scottish researchers under the DISCOVRE project. In 2010 the Life on the Edge Expedition visited some of the GoM sites once again.

In 2010, the GoM went down in history as the site of the Deep-water Horizon tragedy where the largest deep-water oil spill in history gripped the world’s attention. Evidence is emerging that some of the cold-water corals in the GoM may have been damaged by this deep-water oil spill, see report from Penn State University for more information.

Images, video and text have been donated by Dr. Steve W. Ross (Univ. NC-Wilmington), Dr. A. Demopoulos (US Geol. Survey), M. Rhode (Univ. NC-Wilmington) and M.S. Nizinski (NOAA Fisheries).

Background

Authigenic Carbonate

Much of the seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico is muddy, which limits the distribution of many benthic species such as cold-water corals because they cannot find a hard surface to settle onto. The GoM is different to many cold-water coral habitats where the corals settle onto bedrock, boulders or cobbles. Littered throughout the GoM are solid carbonate deposits. At first glance, these blocks look like boulders or bedrock but closer inspection reveals something different.

These blocks form from the precipitation of carbonate minerals. Authigenic means “formed in situ” and these carbonates in the GoM were probably formed by bacteria using hydrocarbons seeping from reserves beneath the seafloor. Now that the amount of seepage in many areas has decreased, these blocks are colonised by diverse communities including thickets of cold-water corals like the reef framework formers Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata.

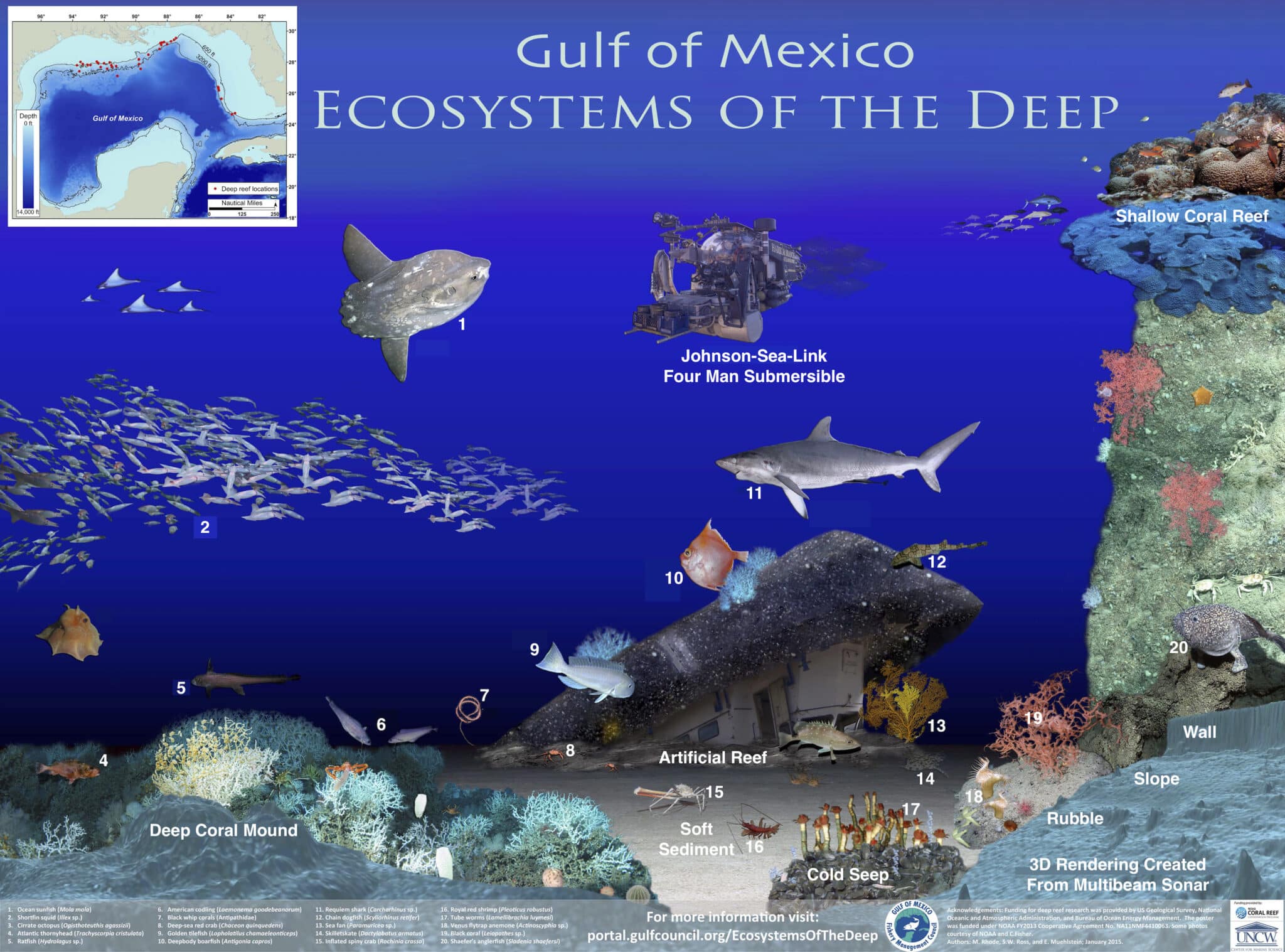

Ecosystems of the Deep

Sandy and muddy bottoms cover most of the deep Gulf of Mexico, but there are also several more complex habitats, and the bottom topography of the Gulf is some of the most rugged in the deep sea. Coral and rocky reefs of the Gulf of Mexico make important contributions to biodiversity, fisheries, and productivity. Only in the last decade has research on the deep coral gardens and ledge systems revealed that deep reefs are widespread in the Gulf and provide habitats to a great variety of organisms, some new to science. Deep corals even populate shipwrecks and oil platform legs. Methane seeping from the sea floor also generates complex habitat and is an ecosystem that is not dependent on energy from the sun. These chemosynthetic communities include bacterial mats, large tube worms, mussels, shrimps, and iceworms that occur only on active methane seeps. The methane can actively bubble from the bottom or if deep and cold enough, it can be frozen (called gas hydrates). Canyons and rocky escarpments further add to habitat diversity in the deep Gulf of Mexico.

Graphic above was developed by the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council and the University of North Carolina Wilmington with funding under NOAA FY2013 Cooperative Agreement No. NA11NMF4410063

1. Ocean sunfish (Mola mola): Ocean sunfish are impressive, strange looking, slow swimming fish that occur in all the world’s oceans, usually far from shore unless stranded. They occur throughout the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. The name comes from their habit of laying on their sides on the ocean surface. Although often spotted at the surface, sunfish dive to deep reefs on occasion. They can grow to 8-10 feet long, and their diet consists mainly of jellyfish and similar pelagic invertebrates. They have no commercial or recreational value in this part of the world.

2. Shortfin squid (Illex sp.): Squids are one of the most important of the pelagic (free swimming) large invertebrates, serving as both vicious predators and in turn are prey to fishes and marine mammals. Since squid move through large distances of the water column (surface to deep-sea), they serve a critical role in moving energy from top to bottom and back again. Squids have been observed over Gulf reefs in huge schools but also often sit on the bottom alone. The genus Illex occurs widely throughout the western Atlantic Ocean, and it is commercially fished in many areas.

3. Cirrate octopus (Opistoteuthis agassizi): The cirrate or dumbo octopus takes its name from the ear-like fins protruding from the body, which it uses as swimming oars. This is a deep living octopus, occurring only in the western North Atlantic and usually deeper than 1000 feet. It is often seen on the bottom or swimming slowly above bottom. It appears to be rare in the Gulf of Mexico, but that could be due to a lack of exploration of the deep.

4. Atlantic thornyhead (Trachyscorpia cristulata): This scorpionfish prefers reef habitat, and it occurs widely in the western North Atlantic Ocean from off New England to the northern Gulf of Mexico, between about 400 to 3600 foot depths. It can grow to a maximum size of about 20 inches. It usually sits on the bottom near or on top of reef material where it waits for prey to swim past.

5. Ratfish (Hydrolagus sp.): Ratfish are also called chimaeras for their family name Chimaeridae, and like sharks and rays, they have a cartilaginous skeleton and lay egg cases. These strange looking fish are often seen swimming above bottom over reefs or sand in depths greater than 1100 feet. Some species grow to about three feet long, and they generally eat small bottom invertebrates and fishes.

6. American codling (Laemonema goodebeanorum): This codling is a moderate sized (maximum length about 12 inches) bottom fish that occurs on reef and sandy habitats and is most common in depths from about 1200 to 2000 feet. It ranges in the western North Atlantic from Canada to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Very little is known about the life history and ecology of this species.

7. Black whip corals (Antipathidae): These unbranched spiral corals have a hard, black skeleton, but the covering flesh is often red to orange. Whip corals occur in the Gulf of Mexico from the shelf edge (250 feet) to the deep sea (at least 3000 feet). They attach to any hard surface, but since the base can be covered in sediment, it appears they are growing out of sediment. They add complexity to the ocean bottom.

8. Deep-sea red crab (Chaceon quinquedens): While red crabs are more common along the US east coast, they occur in the sediments surrounding deep reef habitats in the Gulf in depths of about 1100 to 5000 feet. Red crabs range from Nova Scotia through the US east coast and into the Gulf of Mexico, including the Bahamas and Cuba. This species is fished commercially off the northeastern US, mostly using traps.

9. Golden tilefish (Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps): Golden tilefish are a highly prized food fish and are commercially fished in many places. They occur from Canada to the northern Caribbean, including the Gulf of Mexico (about 250 to 1800 feet, usually deeper than 600 feet in the Gulf). They generally prefer muddy bottoms where they construct elaborate burrow systems, but they can also occur near deep reefs. They eat a wide variety of invertebrates and fishes. This tilefish can reach a little over three feet long and can live up to 35 years.

10. Deepbody Boarfish (Antigonia capros): Deepbody boarfish occur in warmer parts of many oceans, and in the western North Atlantic are known from off New Jersey to Brazil, including Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, in depths of about 200 to 1300 feet. They are a common member of moderate depth reef communities and often occur in schools. They usually eat small crustaceans (shrimps, copepods, etc.) up in the water column.

11. Requiem shark (Carcharhinus sp.): This group of sharks contains a number of species that are most common at shelf depths (less than 600 feet); however, a few species are often observed cruising over the deep reefs of the Gulf of Mexico. They represent a top predator on the food-rich reefs. Sharks are generally overfished in most parts of the world.

12. Chain dogfish (Scyliorhinus retifer): This small shark (usually less than 20 inches long) occurs on both sandy and reef habitats, but is most common on the reefs. Unlike many sharks it does not need to swim constantly and is mostly observed sitting on the bottom. It lays egg cases on rough structures, and young hatch at as size of about four inches. Its overall range is Cape Cod to Florida and the northern Gulf of Mexico to Central America in depths of about 250 to 1800 feet.

13. Sea fan (Paramuricea sp.): There are several species of this octocoral genus in the Gulf of Mexico, but some represent new species. While this coral is not common in moderate depths, it can be fairly abundant on deep (3000 to 8000 feet) reefs of the Gulf. It provides complex structure on the deep reefs. Almost nothing is known of the biology and ecology of these corals.

14. Skilletskate (Dactylobatus armatus): This species, like most skates, inhabits sandy to muddy habitats and is sometimes observed near deep reefs. It is known from off North Carolina through the Gulf of Mexico to Venezuela and from depths of about 1000 to 2000 feet. It is small, less than 12 inches wide, but little else is known about this fish.

15. Inflated spiny crab (Rochinia crassa): Although this long armed crab is often seen on the deep reefs, it is most common walking over nearby sandy to muddy bottom. It occurs from Canada through the Gulf of Mexico to Columbia. Its depth range is usually 220 to 4000 feet.

16. Royal red shrimp (Pleoticus robustus): Besides having a beautiful deep red color, royal red shrimp support a small commercial fishery, but in the Gulf this fishery operates in a fairly limited area. It is considered to be one of the best tasting of wild shrimp, but like most deep-water species it could be easily overfished. This shrimp occurs on sandy bottoms from Canada (rare north of Cape Hatteras) to Columbia to a maximum depth of about 6500 feet. Little is known of its ecology.

17. Tube worms (Lamellibrachia luymesi): This colorful tube worm lives in large aggregations and is characteristic of many Gulf of Mexico methane seep ecosystems that occur in 1500 to 2700 foot depths. It obtains its energy from a chemosynthetic symbiotic relationship with bacteria which use sulfides leaking from the seep as fuel. It grows slowly, reaching lengths of about 10 feet and living up to 250 years. The aggregations form an important habitat that support a number of other deep-sea species. Since these animals do not rely on energy derived from sunlight, they have been of value to science as models of how life may exist on other planets.

18. Venus flytrap anemone (Actinoscyphia sp.): These large anemones, which look and behave something like the land-based venus flytrap, are a common feature on deep reefs of the Gulf. Like most anemones and corals they are predatory and wait for any animals to blunder into the tentacles surrounding the mouth. The tentacles have stinging cells that also cling to the victims. This group of anemones is widespread in the North Atlantic, usually deeper than 1300 feet.

19. Black coral (Leiopathes sp.): Although the exterior flesh can be several colors (red, white) the internal skeleton is black. These black corals provide reef structure and are also home to several other species that climb into their branches. Black corals like this can live to be thousands of years old and one from the Gulf of Mexico has been aged at over 2000 years old. Their skeletons contain rings, like trees, that have chemical signals that allow a reconstruction of past ocean environments. Thus, they are valuable scientific tools as well as important deep reef resources. These corals have been harvested for jewelry, a practice which is usually not sustainable. This black coral is widespread on western North Atlantic deep reefs usually deeper than 1300 feet.

20. Shaefer’s anglerfish (Sladenia shaefersi): Once thought to be rare, this deep-sea anglerfish seems to frequent deep reef habitats from the Caribbean to the Gulf of Mexico and into the western North Atlantic. There is little known about this fish. As with most anglerfish, it sits very still on the bottom waiting for prey to swim buy. It may use the lure ( modified dorsal fin spine) on the top of its head to attract prey.

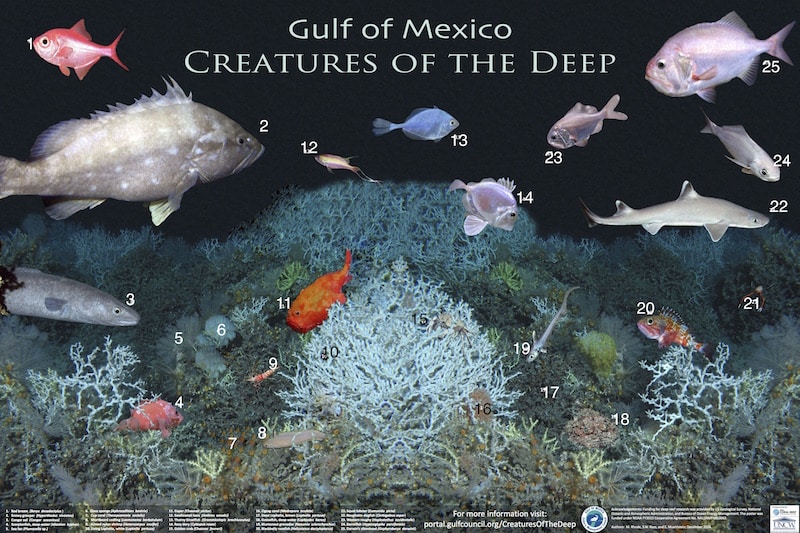

Creatures of the Deep

Fishes and invertebrates of the deep reefs

Deep reef habitats can be composed of coral-built mounds, rocky ledges, and even shipwrecks and are an important component of the Gulf of Mexico. Fishes and invertebrates that occupy these deep reefs are diverse, some are economically important, and many depend exclusively on these ecosystems.

Graphic above was developed by the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council and the University of North Carolina Wilmington with funding under NOAA FY2013 Cooperative Agreement No. NA11NMF4410063

1. Red bream (Beryx decadactylus): This fish, also called an alfonsino, is commercially important in many parts of its range. It occurs worldwide between 330 and 3300 ft. and is usually found between 1000-2000 ft. It prefers rugged, high profile, reef-like habitats where it sometimes occurs in large numbers. It moves from the seafloor up into the water column at night to feed on crustaceans, squids, and small fishes.

2. Snowy grouper (Hyporthodus niveatus): Snowy grouper is a commercially and recreationally important deep reef fish that is susceptible to overfishing. They have been recorded from 65 to 1725 ft. and are most commonly found in depths of 330-1000 ft. It ranges from off the coast of Massachusetts through the Gulf of Mexico and along the Central and South American coasts. Snowy grouper is a top predator, eating mostly fishes, squids, and crabs. Snowy grouper can live to about 30 years old and in US waters spawn between April and July. As in most groupers, it changes sex from female to male as it matures.

3. Conger eel (Conger oceanicus): Conger eels are frequently observed in deep reef habitats, usually sheltering in holes and crevices and can be found off Cape Cod along the US east coast to the north-central Gulf of Mexico and from the estuaries to at least 1900 ft. depths. Fishes make up most of the conger eel’s diet. Like most eels, the larvae of congers are very different from the adults and are long, thin and almost completely transparent. Adults may grow to over 6.5 feet long, and in some places conger eels are valued as food fish.

4. Scorpionfish, deep-water (Idiastion kyphos): Very little is known about this small deep-water scorpionfish. It was only recently observed on deep reefs of the Gulf of Mexico and has also been reported from deep reefs off the southeastern US coast, scattered locations in the Caribbean Sea, and off Venezuela in depths of 750-2050 ft. The scarcity of information on these fish is likely because they hide in coral and rocks, making them hard to sample.

5. Sea fan (Plumarella spp.): Several species of corals in this genus occur on deep reefs from North Carolina to the Straits of Florida and into the eastern Gulf of Mexico in depths of about 600 to 3000 ft. Although little is known of the life history of these octocorals, they add structure to the deep reefs that benefits other animals.

6. Glass sponge (Aphrocallistes beatrix): This deep-water sponge is called a glass sponge because it has a translucent body and its structure is composed of spines made of silicon. It is often covered by attached yellow soft corals. It occurs on deep reefs on both sides of the North Atlantic Ocean, and in the western Atlantic it occurs from North Carolina into the central and eastern Gulf of Mexico to Brazil. Glass sponges may live for hundreds of years, and some species have chemical compounds that have medicinal benefits. Although there is very little data on the biology and ecology of this sponge, it contributes to the habitat complexity of deep reefs.

7. Cup coral (Thecopsammia socialis): This small, mostly yellow/orange hard coral has a single polyp, unlike colonial corals, which are aggregations of many polyps. It lives on rocks and dead corals in a depth range of about 700 to 3000 ft. and has been observed off North Carolina to the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Almost nothing is known of its biology and ecology.

8. Shortbeard codling (Laemonema barbatulum): This fish, related to cods, occurs from Canada through the central and eastern Gulf of Mexico and off northern Brazil from 160 to 5300 ft. (most common from 1000-1300 ft.). There is little known of the life history of this species, but it commonly occurs on deep reef, canyon, and nearby habitats. It is one of the more abundant bottom fishes of the continental slope.

9. Armed nylon shrimp (Heterocarpus ensifer): In some parts of its range this small shrimp may have potential commercial importance but generally not in US waters. It occurs widely in the North Atlantic Ocean and other oceans, and in the western Atlantic it has been recorded from North Carolina to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico, most common in 1000-2000 ft. depths. While mostly known to live on sand or mud bottom, it has also been commonly observed around deep reefs off the southeastern US and in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Females grow to larger sizes than males and have bright blue eggs that are spawned over a long period of time.

10. Living Lophelia, white (Lophelia pertusa): This hard, branching, colonial coral occurs nearly world-wide and is the most common structure forming deep-sea coral. In addition to attaching to rocks and unnatural structures (shipwrecks, oil platforms), it forms mounds and ridges that can be over 330 feet tall. It is the foundation for many deep reefs, creating significant complex habitat that other animals use. In US waters, Lophelia is most common off the southeastern US and in the north-central to eastern Gulf of Mexico from about 650 to 2600 ft. The living coral is bright white because, unlike many shallow corals, it does not have a symbiotic partnership with algae. Though hard, Lophelia is also brittle and can be damaged easily.

11. Gaper (Chaunax pictus): These globular red fish are often observed perched on reef-like habitats of the continental slope. In the western Atlantic, they occur from South Carolina to the eastern Gulf of Mexico to Guatemala, including the Bahamas and the Caribbean Sea in depths from 900-2600 ft. There is little known of the biology and ecology of this fish, but it is likely an ambush predator hiding and waiting until prey swim too close, or it may even attract prey.

12. Swallowtail bass (Anthias woodsi): This beautiful fish, related to groupers, occurs on continental slope reefs off Virginia through the southeastern US and into the eastern Gulf of Mexico in depths of 300-1500 ft. Like the groupers, it is likely hermaphroditic, but little else is known of this secretive species.

13. Thorny tinselfish (Grammicolepis brachiusculus): A goofy looking fish, the thorny tinselfish is often observed swimming about the deep reefs, sometimes in small schools. It has a world-wide distribution, but in the western Atlantic it ranges as far north as Georges Bank and south into the north-central and eastern Gulf of Mexico from 800 to 3000 ft. It seems to be more common on deep reefs of the Gulf of Mexico than deep reefs elsewhere. As with many deep-water species, little is known of its ecology or biology.

14. Rosy dory (Cyttopsis rosea): The rosy dory has a large world-wide distribution. In the western Atlantic, it occurs from Canada and the southeastern US through the northern Gulf of Mexico and into the western Caribbean to northern South America in 500 to 2400 ft. depths. It feeds on small fishes and swimming crustaceans. It is usually seen alone over both reef and sandy habitats.

15. Golden crab (Chaceon fenneri): Golden crab support a small commercial trap fishery in the Atlantic Ocean off Florida, though some may be caught in the Gulf of Mexico. This large crab occurs from the southeastern US to Brazil. It appears to be drawn to deep rocky and coral habitat, where it often buries deep within the coral matrix. It is suspected that golden crab have a smaller population than other similar crabs.

16. Zigzag coral (Madrepora oculata): This fragile, colonial stony coral is often pink colored and can be attached to rocks or to dead Lophelia coral. It provides significant reef structure in some locations but does not form the large reefs or bioherms like Lophelia. It occurs on both sides of the Atlantic and in the western Atlantic from North Carolina through the Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean Sea south to Brazil. Its overall depth distribution is 180-6400 ft., but is usually deeper than 1000 ft. in the Gulf and off the southeastern US.

17. Dead Lophelia, brown (Lophelia pertusa): As Lophelia grows and ages the lower branches often die, sometimes because they are smothered by sediments. This is a natural process and does not necessarily signal a problem for these reefs but, the ecology of Lophelia is not well understood. This dead framework provides hiding places for various animals and attachment sites for other corals and sponges.

18. Goosefish, deep-water (Lophiodes beroe): There are several species of deep-water goosefishes, but this species seems to be most common on the deep reefs, ranging from North Carolina to the northeastern Gulf of Mexico and along the western Caribbean Sea to northern South America in depths of 1130-2825 ft. This well camouflaged fish with a huge mouth is in the angler fish family. It sits and waits for prey to swim by; it uses the long lure on the top of its head to attract prey. This species is more abundant than once thought, but its biology and ecology are still poorly understood.

19. Bluntsnout grenadier (Nezumia sclerorhynchus): Primarily occurring off the US east coast and in the eastern Atlantic, this rattail species was only recently observed in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. It can occur in a depth range of 425 to 3600 ft. and is most common in 1475-2400 ft. It tends to be more frequent over complex, reef-like habitats, and it consumes a variety of small crustaceans and worms.

20. Blackbelly rosefish (Helicolenus dactylopterus): Blackbelly rosefish is named for the black internal lining of the belly which cannot be seen externally. This is one of the most common fishes on the continental slope and is commercially important in some parts of its range. It occurs on both sides of the Atlantic, in the western Atlantic from Canada through the northern Gulf of Mexico and along the western Caribbean to Argentina, usually in 360-2410 ft. depths. Although it is often seen on sandy bottoms, it seems most abundant on complex habitats, where it perches on the bottom awaiting prey to swim by. It can live to be nearly 40 years old, and it feeds on a wide variety of bottom and near bottom invertebrates and fishes.

21. Squat lobster (Eumunida picta): This distinctive squat lobster is one of the most common of the larger deep reef invertebrates. It occurs from off Massachusetts through the Gulf of Mexico and western Caribbean to Columbia over a depth range of about 275 to 7215 ft. It is often seen perching motionless with claws outstretched as high as possible on rocks or deep coral branches, and it catches fishes, squids or other animals that swim too close.

22. Roughskin dogfish (Cirrhigaleus asper): The roughskin dogfish has a world-wide distribution, and in the western Atlantic occurs from off North Carolina to southern Florida, scattered locations in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, and off southern Brazil and Argentina in depths of 240 to 2000 ft. It is likely to be found in more of the western Atlantic than is currently known but, it is difficult to collect because of its association with deep reefs. It rarely grows beyond three feet in length and is likely a top predator on deep reefs, feeding mostly on fishes, squids and octopi.

23. Western roughy (Hoplostethus occidentalis): In the same genus as the commercially important orange roughy (H. atlantica), this small roughy can be abundant on deep reefs of the region. This fish only occurs in the western North Atlantic where it is known from the Gulf of Maine, off the southeastern US, into the north-central and eastern Gulf of Mexico, and the western Caribbean to northern South America in 450-1800 ft. depths. Its lack of commercial importance and the limited data on the species are because it is difficult to capture in its deep reef habitat. It generally feeds on small crustaceans and probably migrates up into the water column at night to feed, like many other roughies.

24. Barrelfish (Hyperoglyphe perciformis): Barrelfish occur from the Gulf of Maine (rare) along the US east coast to the north-central Gulf of Mexico. The juveniles occur at the surface often taking shelter under floating plants or debris (like barrels, hence the common name), but adults occupy near-bottom waters to about 1312 ft. This free swimming fish is often seen in schools around Gulf deep reefs. It feeds on small fishes and various invertebrates. Barrelfish can grow to about three feet in length and have minor commercial value as food fish.

25. Darwin’s slimehead (Gephyroberyx darwinii): This roughy species is larger than the western roughy and is commonly observed around rocky deep reefs where it takes shelter in holes and crevices. It could have potential commercial interest but is generally not seen in great abundance. It has a world-wide distribution and in the western Atlantic occurs from the Gulf of Maine through the southeastern US, the north- central and eastern Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean and northern South America. Its depth range is from 230 to 2100 ft., and it is most common from 650-1650 ft. It eats mostly small shrimps and fishes.

- Brooke S, Schroeder WW (2007) State of Deep Coral Ecosystems in the Gulf of Mexico region: Texas to the Florida Straits. In: Lumsden SE, Hourigan TF, Bruckner AW, Dorr G (Eds). The State of Deep Coral Ecosystems of the United States. NOAA Technical Memo. CRCP-3. Silver Spring MD, pp 271-306

- Cairns SD (1978) A checklist of the ahermatypic scleractinia of the Gulf of Mexico, with a description of a new species. Gulf Research Reports 61: 9-15

- Continental Shelf Associates (2007) Characterization of Northern Gulf of Mexico deep-water hard bottom communities with emphasis on Lophelia coral. US Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, New Orleans, LA. OCS Study MMS 2007–044, 169 pp + appendices

- Cordes EE, Carney SL,Hourdez S, Carney RS, Brooks JM, Fisher CR (2007). Cold seeps of the deep Gulf of Mexico: community structure and biogeographic comparisons to Atlantic equatorial belt seep communities. Deep-Sea Research I 54: 637-653

- Moore D, Bullis H Jr. (1960) A deep-water coral reef in the Gulf of Mexico. Bulletin of Marine Science 10: 125–128

- Newton CR, Mullins H,Gardulski F, Hine A , Dix G (1987). Coral mounds on the west Florida slope: unanswered questions regarding the development of deepwater banks. Palaios 2: 359–367

- Reed JK, Weaver DC, Pomponi SA (2006) Habitat and fauna of deep-water Lophelia pertusa coral reefs off the southeastern US: Blake Plateau, Straits of Florida, and Gulf of Mexico. Bulletin of Marine Science 78: 343-375

- Schroeder WW (2002) Observations of Lophelia pertusa and the surficial geology at a deep-water site in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Hydrobiologia 471: 29–33

- Schroeder WW (2007) Seafloor characteristics and distribution patterns of Lophelia pertusa and other sessile megafauna at two upper-slope sites in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. US Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, New Orleans, LA. OCS Study MMS 2007–035, 56 pp

- Schroeder WW, Brooke SD, Olson JB, Phaneuff B, McDonough JJ III, Etnoyer P (2005) Occurrence of deep-water Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata in the Gulf of Mexico. In: A. Freiwald, J.M. Roberts (Eds). Cold-water Corals and Ecosystems. Springer, Berlin, pp 297–307

- Sulak KJ, Brooks RA, Luke KE, Norem AD, Randall M, Quaid AJ, Yeargin GE, Miller JM, Harden WM, Caruso JH, Ross SW (2007) Demersal fishes associated with Lophelia pertusa coral and hard-substrate biotopes on the continental slope, northern Gulf of Mexico In: George RY, Cairns SD (eds). Conservation and adaptive management of seamount and deep-sea coral ecosystems. University of Miami. 324 pp

- Williams B, Risk MJ, Ross SW, Sulak KJ (2006) Deep-water antipatharians: proxies of environmental change. Geology 34: 773-776

- Williams B, Risk MJ , Ross SW, Sulak KJ (2007) Stable isotope data from deep-water Antipatharians: 400-year records from the southeastern coast of the United States of America. Bulletin of Marine Science 81: 437-447

- Davies AJ, Duinevald GCA et al. (2010) Short-term environmental variability in cold-water coral habitat at Viosca Knoll, Gulf of Mexico. Deep Sea Research Part 1-Oceanographic Research Papers 57(2):199-212

- Cordes EE, McGinley MP et al. (2008) Coral communities of the deep Gulf of Mexico. Deep Sea Research Part 1-Oceanographic Research Papers 55(6):777-787

Angola

New discoveries of living corals