The deep

Environment

The ocean covers 71% of the surface of the earth and affects every aspect of human life from the food we eat to the air we breathe. Over half of the surface of the earth is covered by water more than 1000 m deep – it is often said we know more about the surface of the moon than we do about the deep ocean floor.

We began to learn about life in the deep ocean in the 19th century. Around this time Edward Forbes at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland suggested that the seabed below 600 m was lifeless. This idea stimulated others – could it really be true that no life existed over huge areas of the planet?

Around this time others were exploring the deep-sea, often in search of new sea passages or to survey the route for submarine cables. These deep-sea pioneers sometimes found animals caught on the sounding lines they used to measure water depth. In Norway Michael Sars and his son G.O. Sars found almost 100 species living below 600 m – including a live stalked sea lily that was only was only known from fossils.

In the UK, Charles Wyville Thomson became fascinated by the question of whether life could exist in the chilly waters of the deep-sea and whether the deep-sea was a refuge for species thought to be extinct. He visited Michael Sars in Norway and saw the animals dredged from deep in the fjords. On his return to Britain, Wyville Thomson and W.B. Carpenter organised an expedition with the Royal Society of London and using ships from the British Royal Navy (H.M.S. Lightning and H.M.S. Porcupine) set out in the summers of 1868-1870. These early cruises dredged down to over 4000 m – a fantastic achievement at the time.

Now convinced that life was present at the greatest ocean depths, Wyville Thomson organised the world-famous Challenger expedition using the H.M.S Challenger to circumnavigate the world between 1872 and 1876. As well as finding animal life at over 5000 m depth, this expedition examined the temperatures and salinities of the ocean and laid the foundations for the science of oceanography.

The deep-sea is an undiscovered world. We have explored the highest mountains and deepest valleys on land but the deepest portion of the ocean, the Mariana Trench (Pacific Ocean), has only been explored a few times, once in 1960 the US Navy dived almost 11 km beneath the surface using the ‘Trieste’, and a couple of times in the 1990s using the remotely operated vehicle ‘KAIKO 7000II’. In 2009 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution dived their robotic submarine Nereus to an amazing 10,902 m in the Challenger Deep, the deepest region of the Mariana Trench.

To this day, the 1960 Trieste dives are the deepest people have ever been within the oceans – the largest environment on Planet Earth.

| Click here for a fly-through animation of the Mariana Trench |

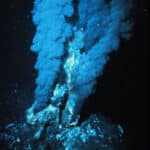

Who knows what other wonders are hidden in the deep-sea? Scientists have made a start but have investigated less than 4% of the deep seabed. Only as recently as 1977 did scientists discover hydrothermal vents with their unique communities of marine life. Many of the large cold-water coral reefs featured on this site were only discovered in the last 10 or 15 years.

The deep-ocean is often thought of as a stable environment, characterised by cooler temperatures than the surface waters. Sunlight is quickly absorbed by seawater, with very little light penetrating beyond the first 200 m. Plants cannot grow without sunlight, so plant life is restricted to maximum depths of approximately 50-100 m.

The ocean dominates the southern hemisphere, covering almost 80% of the surface. There is less ocean in the northern hemisphere, but it still covers 61% of the surface. The Pacific Ocean is the largest water body on the earth, covering almost a third of the earth’s surface (a massive 180 million square miles).

On average the ocean is 4000 metres deep, and over 84% of the ocean bottom is found deeper than 2000 m. The greatest depth reached by a human free diver is just 214 m. Even breathing sophisticated mixtures of gases, the deepest human dive is currently 610 m by a US Navy diver off La Jolla California in 2006, conducted in a specialised hard suit.

For now, routine diving to the depths of the deep-ocean is impractical, and scientists rely on sophisticated technology to investigate the deep sea. To visit abyssal depths of several thousand metres, expensive and technologically advanced submarines are needed.