The deep

Science

Until relatively recently, scientists studied the deep-sea floor by dredging and trawling to bring samples back to the surface. This was difficult work that damaged the seabed, animals living on the seabed, and the fauna in the samples themselves. Dredging is still used today, but in conjunction with new technology, sample collection can be targeted, reducing collateral damage.

The science of the deep has changed dramatically. Advanced acoustic mapping allows scientists to map large areas of seabed and then use video surveys or submersibles to examine the ecosystems on the seafloor.

These technologies have revealed spectacular cold-water coral ecosystems around the world. However as new coral habitats are discovered, the surveys often show that reefs have been physically damaged, most often by bottom trawling. In a recent study, Norwegian researchers estimated that up to half of Norway’s cold-water coral reefs were already damaged by bottom trawling.

Researching the deep sea is a major challenge for scientists. Studying deep-sea habitats is time consuming and expensive so research expeditions can be few and far between. A scientific finding should be replicated so that more evidence can be gathered to support predefined arguments or ‘hypotheses’. Without replicating observations and experiments, hypotheses cannot be properly tested. To deal with this, scientists have developed techniques to gather as much information as possible from the short times they have access to deep-sea environments.

A broad range of techniques, from localised sampling to large-scale mapping, are needed to understand deep-sea environments. Researchers often push the forefronts of new technologies to gather the information they need. Here we’ll look at different ways of surveying the seafloor before seeing how to collect samples from the depths of the ocean and record deep-sea animals and their environment over time.

Mapping

On land we can use aerial photography or satellite images to map huge areas, from city streets to tropical rainforests. But we can’t see through thousands of feet of seawater to the deep seabed. Though seawater quickly blocks electromagnetic radiation, it’s good at transmitting sound waves – whales can communicate with each other across vast stretches of ocean with low frequency ‘songs’. This means that it’s possible for us to build a picture of the seafloor using sound waves.

These acoustic mapping technologies developed rapidly after the Second World War using sonar technology. Sonars rely on measuring the speed and strength of a reflected acoustic signal. Sonars have many uses, from depth sounders and fish finders to multibeam and sidescan sonars used to map the seafloor.

Depth sounders, originally developed in the 1920s, operate by measuring the time it takes for a pulse of sound fired from the hull of a ship to bounce back from the seafloor. Multibeam echosounders, developed in the 1960s, work on the same principle but, instead of a single beam of sound, they often use over a hundred beams of sound that fan out to cover a swathe of seafloor. As well as measuring the depths across this swathe, multibeam echosounders also record the intensity of sound returned to the ship. This shows how much sound energy is backscattered from the seafloor and can be used to generate an acoustic picture. So, as well as accurately mapping water depths across a swathe of seafloor, multibeam sonars also record backscatter images, giving some idea of the nature of the seabed.

Sidescan sonar systems, developed in the 1960s allow scientists to dynamically image the seabed, a form of aerial photography in the sea. Sidescan systems are usually towed behind ships on a specially designed towfish to get them closer to the seafloor. The resolution of sidescan sonars relates to their frequencies. Generally speaking, higher frequency systems produce higher resolutions but cover smaller areas than lower frequency systems.

Both multibeam and sidescan sonars are used to survey cold-water coral reefs. Because the reefs can form mounds growing up from the seafloor, they can even be seen on the depth records (or bathymetries) produced by multibeam sonars. Multibeam sonars are one of the most exciting technological developments in cold-water coral research because they allow researchers to map large areas of seafloor and search out unknown reef structures.

Visual surveys

Video surveys have become the second key tool in deep-sea research. After a successful mapping program, video cameras and lights will be lowered to investigate key features or targets identified from the mapping programme.

Cameras come in all shapes and sizes, from those lowered from ships on cables to ones mounted on submersibles and ROVs. They all perform the same function, and that is to beam images back to the waiting observers on the surface or in the submersible.

As the sea is a constantly moving medium, it is difficult for a ship to remain in a single place, so many visual surveys are conducted in the form of transects. The ship is controlled along a specific path and using complex mapping software this track can be overlaid with previous mapping efforts to produce an accurate representation of the area. These data can then be used to focus our attention even further, allowing researchers to select specific areas for sampling and to reduce collateral damage when samples are taken.

Sampling

Gathering a sample from the deep seafloor is a difficult and arduous task. Regular sampling is often impossible due to the high costs associated with research expeditions to deep-sea environments. Large ships with a specialised crew are needed to deploy the sampling equipment and retrieve the sample.

In the early days, researchers relied on small trawls and dredges to scoop samples from the seafloor. But dredges and trawls have to be towed on long wires to reach the seafloor and may not always give a true picture of what lives there. Imagine trying to build a picture of the inhabitants of London by flying across in a balloon and using a bucket lowered on a rope to catch the people beneath. Purely by chance you might catch a policeman and a traffic warden – and assume that the population of London was just policeman and traffic wardens!

Without samples we cannot understand life in the deep ocean but gathering truly representative samples is a difficult task.

Landers and seafloor observatories

Landers

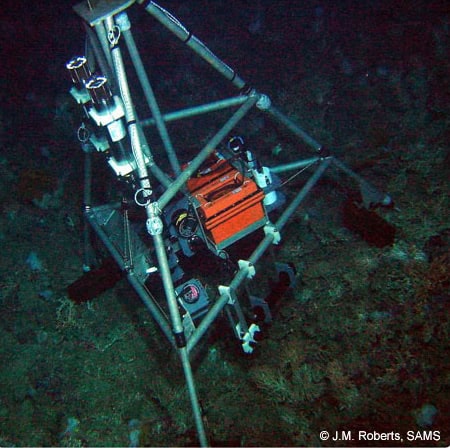

A lander is a system that can be ‘landed’ on a remote or inhospitable location to take measurements before being brought back so the information gathered can be recovered. We have learned about the surface of the Moon and Mars using landers sent through space. In a similar way, marine scientists use landers that can be sent to the deep seabed to carry out a pre-determined work programme.

These benthic landers work on a simple principle. When they are sent to the seabed they carry ballast weights to hold them in place. Special release mechanisms hold these ballast weights until they are triggered to drop them. Once dropped the landers become buoyant and float back to the surface where they can be collected by a research ship.

There are many advantages to using benthic landers. Research ships are very costly and can only work in good weather conditions, often just in the summer months. Long-term landers can be deployed in the summer and left in place for many months, sometimes over a year, gathering information on how the deep-sea environment varies through the seasons. A lander will take a few hours to set in place but will gather information continuously for long periods of time. Unlike manned submersibles or ROVs, landers are less likely to disturb animals at the seabed so are a good way of recording their behaviour over time.

Benthic landers have been put to many uses from time-lapse photography to detailed study of the chemistry of the deep seabed – limited only by the instruments that are suitable to use on them. A major disadvantage of the benthic lander approach is that they are limited by the on-board power and memory any one lander can carry.

Seafloor observatories

A lander is a system that can be ‘landed’ on a remote or inhospitable location to take measurements before being brought back so the information gathered can be recovered. We have learned about the surface of the Moon and Mars using landers sent through space. In a similar way, marine scientists use landers that can be sent to the deep seabed to carry out a pre-determined work programme.

These benthic landers work on a simple principle. When they are sent to the seabed they carry ballast weights to hold them in place. Special release mechanisms hold these ballast weights until they are triggered to drop them. Once dropped the landers become buoyant and float back to the surface where they can be collected by a research ship.

There are many advantages to using benthic landers. Research ships are very costly and can only work in good weather conditions, often just in the summer months. Long-term landers can be deployed in the summer and left in place for many months, sometimes over a year, gathering information on how the deep-sea environment varies through the seasons. A lander will take a few hours to set in place but will gather information continuously for long periods of time. Unlike manned submersibles or ROVs, landers are less likely to disturb animals at the seabed so are a good way of recording their behaviour over time.

Benthic landers have been put to many uses from time-lapse photography to detailed study of the chemistry of the deep seabed – limited only by the instruments that are suitable to use on them. A major disadvantage of the benthic lander approach is that they are limited by the on-board power and memory any one lander can carry.

- Benthic landers and seafloor observatories for cold-water coral research (Roberts et al. 2005)

- Roberts JM, Peppe OC, Dodds LA, Mercer DJ, Thomson WT, Gage JD and Meldrum DT (2005) Monitoring environmental variability around cold-water coral reefs: the use of a benthic photolander and the potential of seafloor observatories. In: Freiwald A & Roberts JM (eds) Cold-Water Corals & Ecosystems. Springe, Berlin Heidelberg. pp 483-502

- Review article of benthic chamber landers (Tenberg et al. 1995)

- Tengberg A, De Bovee F, Hall P, Berelson W, Chadwick D, Ciceri G, Crassous P, Devol A, Emerson S, Gage J, Glud R, Gratiottini F, Gunderson J, Hammond D, Helder W, Hinga K, Holby O, Jahnke R, Khripounoff A, Lieberman S, Nuppenau V, Pfannkuche O, Reimers C, Rowe G, Sahami A, Sayles F, Schurter M, Smallman D, Wehrli B, De Wilde P (1995) Benthic chamber and profiling landers in oceanography – A review of design, technical solutions and functioning. Progress in Oceanography 35: 253-294

- Technology has developed to such an extent that people are now installing seafloor observatory systems which are connected by cable to the mainland. So far, there are three main initatives:

MARS, USA

NEPTUNE, Canada

ESONET, Europe

Researching the deep is dominated by two exotic pieces of equipment. Manned submersibles allow scientists to physically visit the deep-sea, practically immersing themselves in the environment. They are expensive and rarely used by the vast majority of scientists. ROVs on the other hand, are widely available and when used effectively can be almost as good as a submersible.

Manned Submersibles

Manned submersibles were often used in deep-sea research before the development of ROVs. They still have a major role to play in deep-sea research, as nothing can replace the experiences gained by actually visiting a deep-water environment.

There are only a few operational deep-sea research submersibles. The first notable submersible was the Bathysphere, an American submersible developed in the 1930s. Technology has advanced a long way since then, with the development of the highly successful Alvin submersible which routinely conducts 150 dives a year and the French submersible Nautile (Ifremer) which can operate in 97% of the world’s oceans.

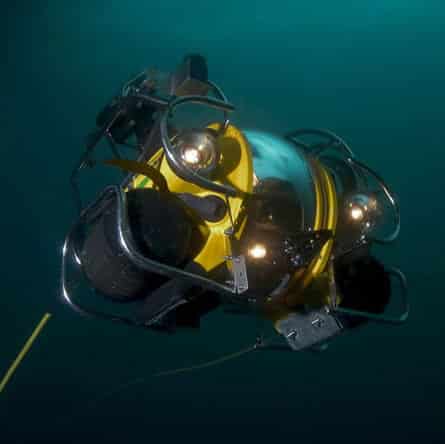

Remotely operated vehicles

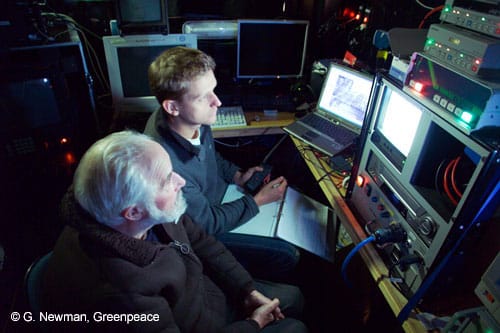

Modern ROVs are lowered into the water connected to the surface ship by an umbilical cable. This cable sends the pilot’s commands, as well as feeding back imagery of the sea floor.

Deploying a deep-sea ROV is not an easy task. Depending on location, an ocean going vessel is required, fitted with a handling system that deploys and retrieves the ROV, a control console which allows the pilot to fly the ROV and a cable and telemetry system that links the ROV with the console.

ROVs can collect a wide variety of different data, including video and still imagery and if fitted with the relevent equipment can collect samples and carry a range of different sensors. Deep-water ROVs give scientists incredible opportunities not just to survey the deep sea, but to carry out experiments in one of the most inaccessible environments on earth. Remotely operated vehicles or ‘ROVs’ are unmanned submarines fitted with an array of sensors, cameras and lights. Since the crew remains on the surface ship, ROVs are inherently safer than manned submersibles.

The deep sea is a vastly undiscovered ecosystem on our planet. Dr. Don Walsh is one of the first people to go to the deepest part of the ocean, the Marianas Trench. The expedition was run by the United States Navy who bought the Trieste Project from the inventors in 1958. Trieste is a deep diving Bathyscaphe that is able to carry two individuals to one of the most extreme locations on the planet, the bottom of the ocean.

Dr. Don Walsh started his ocean exploration career before becoming formally educated in Oceanography. He did his Ms and PhD 8 years after his dive on the Trieste expedition. Since then he has been educating and consulting globally on a variety of ocean-related issues. From his first dive, Walsh has seen submersibles grow in popularity and be replaced with ROVs and AUVs. He predicts that remote controlled submersibles are helpful tools in deep-sea ocean exploration.

As for the future of seep sea exploration, “We need to fully explore that 90% of the World Ocean that is still unexplored…The deep trenches are the real frontier and we [need] to do much more in those places which represent only 2% of the seafloor area.”