Threats

Threats

Many cold-water corals grow slowly and can be very long-lived, making them susceptible to natural damage and human activities. In some cases cold-water corals and the reefs they form may take hundreds or thousands of years to recover. See the sections below to find out how each threat could affect cold-water coral ecosystems.

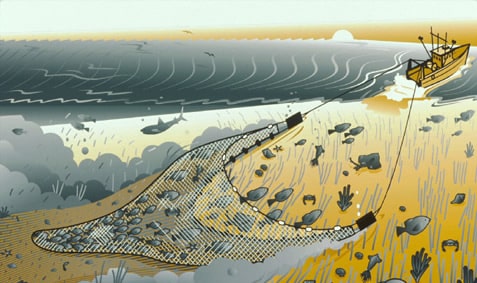

Humans have always exploited the fruits of the sea, the amazing diversity and sheer abundance of food and materials have provided extensive resources and commercial income for many years. Now, there is growing concern about the impacts of fishing on the marine environment.

It is now common knowledge that fish stocks have declined significantly and the blame is usually attributed directly to intensive over-fishing. But there may be other contributory factors in the collapse, such as accidental by-catch and habitat destruction. Indirectly, these factors may disrupt nursery grounds and remove shelter for many fish species, reducing the input of new individuals and so reducing fish stocks even further.

In the past fishermen would try to avoid contacting rough ground such as cold-water coral reefs as they would shred their nets. This is highlighted by the French biologist Joubin. In 1915 he published a paper entitled: “Les coraux de mer profunde nuisibles aux chalutiers.” Translated it reads, “Deep-water corals, a nuisance for trawlers”. However, as offshore fishing vessels and the trawl gear they use have grown in size, it has become clear that deep-water trawling may have caused significant damage to cold-water coral ecosystems around the world.

The global catch of marine fish is big business, in 2001, the estimated value was $75 billion USD. Bottom trawling fishing does not represent a large component of that catch, and is unlikely to exceed $300-400 million USD annually (0.4%).

Source:

* Gianni, M. (2004) High seas bottom trawl fisheries and their impacts on the biodiversity of vulnerable deep-sea ecosystems. Report for ICUN, NRDC, WWF, Conservation International.

The greatest potential threat to cold-water coral reefs from oil and gas drilling would be the smothering effect of any drill cuttings released near the reefs. However, there is almost no information on how cold-water corals respond to being exposed to sediment and people rely on drawing parallels from work carried out on tropical coral species.

In many parts of the world, individual oil companies and the countries that license oil exploration follow tightly controlled procedures to limit environmental impact. Generally speaking, seabed impacts are confined to a small area. However, if drilling is not well regulated and engineering works or discharges take place too close to cold-water coral reefs, then these activities could smother, stress or physically damage the corals and their inhabitants.

Cold-water corals have a few surprises though. In the late 1990s while debate raged over the potential damage deep-water drilling could inflict on cold-water corals, they were discovered growing on oil platforms in the North Sea – even on the Brent Spar, a cause célèbre in its own right (you can read more about the Brent Spar case from Shell and Greenpeace along with a summary on Wikipedia).

Further work has shown that many Lophelia colonies have been growing close to sites where drill cuttings have been released over the years. ROV surveys have shown that in some places half a colony has been smothered by drill cuttings – but the other half is apparently healthy.

Much more work is needed to understand how reef framework-forming corals like Lophelia pertusa deal with sediment exposure before we can judge how sensitive they may be. After all, cold-water coral frameworks trap sediments, and many corals have been photographed growing on rippled sandy seabeds where the corals are likely to tolerate sediment exposure.

- Bell N, Smith J (1999) Coral growing on North Sea oil rigs. Nature 402: 601

- Gass SE, Roberts JM (2006) The occurrence of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia) on oil and gas platforms in the North Sea: Colony growth, recruitment and environmental controls on distribution. Marine Pollution Bulletin 52: 549-559

- Roberts JM (2000) Full effects of oil rigs on corals are not yet known. Nature 403: 242

- Roberts JM (2002) The occurrence of the coral Lophelia pertusa and other conspicuous epifauna around an oil platform in the North Sea. Underwater Technology 25: 83-91

- Rogers AD (1999) The biology of Lophelia pertusa (Linnaeus 1758) and other deep-water reef-forming corals and impacts from human activities. International Review of Hydrobiology 84: 315-406

Shaking foundations

Ocean Acidification shakes the foundation of cold-water coral reefs.

The longest-ever simulation of future ocean conditions shows that the skeletons of deep-sea corals change shape and become 20-30% weaker, putting oases of deep-sea biodiversity at risk.

Because the ocean absorbs much of the extra carbon dioxide produced by human activities, the chemistry of seawater is changing, a process known as ocean acidification. Scientists at Heriot-Watt University, publishing in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, have simulated this process in the laboratory: while corals appear to feed and grow well, this hides fundamental changes in the structure of their skeletons. These changes put the whole reef structure at risk.

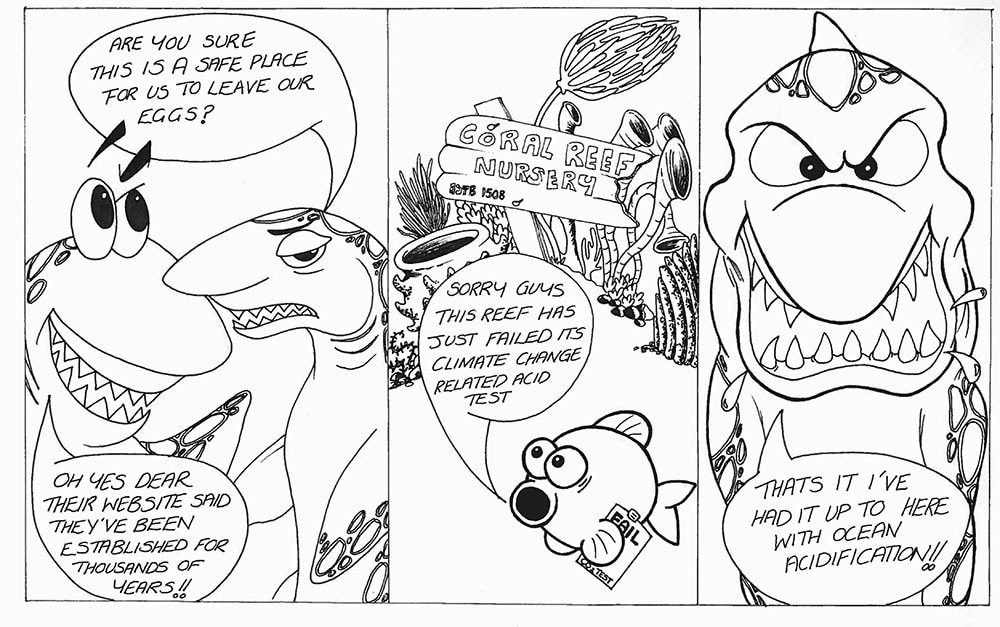

Few people are aware that more than half the coral species known to science are found in deep-waters growing in chilly temperatures, and that spectacular reefs supporting a wealth of other marine life grow in the cold waters of the North Atlantic Ocean.

Scientists at Heriot-Watt University painstakingly kept Scottish deep-water corals for a year in purpose-built aquaria. Carefully designed experiments, of the highest international standard, made it possible to simulate precisely a range of future ocean conditions with higher carbon dioxide and warmer temperatures. They discovered that the coral skeleton changed in structure and shape, and that the dead coral became much more easily snapped and damaged.

“The very foundation of the reefs is where the biggest impacts may be seen. Live corals are standing on the shoulders of their dead parents and grandparents, and we see that ocean acidification can start to dissolve dead coral skeleton,” explains Dr Sebastian Hennige, lead author of the new study. “This makes them weaker and more brittle, like bones with osteoporosis, and means that they may not be able to support the large reefs above them in the future”.

“This is bad news for deep-coral reefs”, says Professor Murray Roberts, who led the project team, “There is no scope for dead coral to adapt to ocean acidification. Our results strongly suggest that deep coral reef structures as we know them may be at serious risk of disappearance within our children’s lifetimes – and the role these structures play in the ecosystem, providing habitat for thousands of other species, including places for sharks to lay their eggs, will be lost.”

For more information on how corals may be impacted by climate change please contact Sebastian Hennige at s.hennige@hw.ac.uk

Global warming

The temperature of the earth and its oceans has been increasing since the mid 20th century, because of increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, mainly from human activities such as fossil fuel burning and deforestation. According to the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), sea surface temperatures rose by almost 1°C from 1906-2005, and the rate of increase is getting quicker. This warming not only affects the surface waters, but these increases have penetrated to depths of at least 700 m, well within the depth zone of cold-water corals.

As cold water corals are restricted to fairly narrow temperature ranges, any changes may have a dramatic effect on their health and survival. Recently, laboratory experiments on Lophelia pertusa colonies showed that an increase in temperature of just 5°C from the temperature they are used to, caused a three-fold increase in their energy demands. This increased energy demand would have to be matched by an increased food supply to the corals to enable them to grow and survive. No one knows whether food supply to these corals will keep pace, or whether food production in the oceans will be changed by these temperature changes – if food becomes limiting the corals may simply starve.

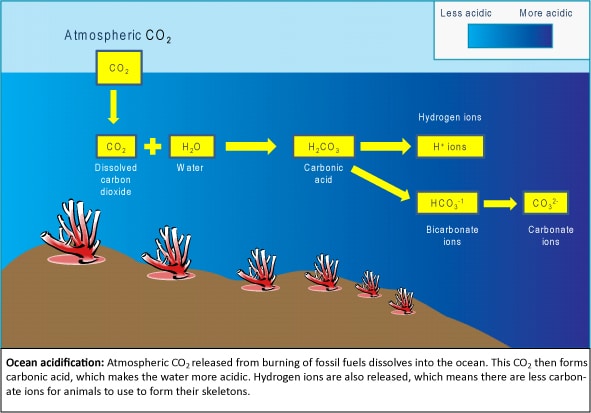

Ocean acidification

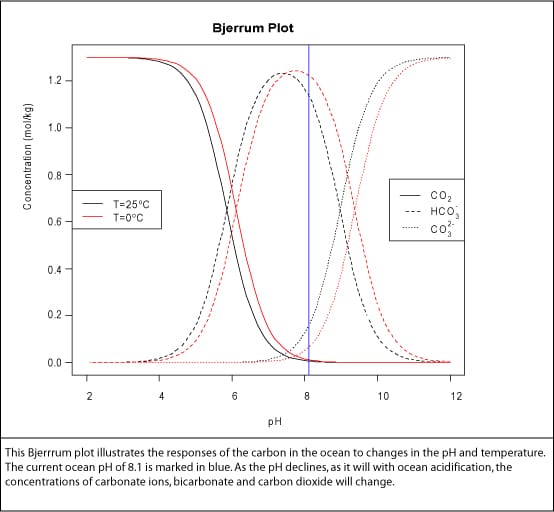

As well as global warming, there is a second problem facing our seas which is potentially catastrophic to all marine organisms that, like corals, produce limestone shells or skeletons – ocean acidification. Since the industrial revolution began, vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) have been pumped into the atmosphere, increasing the concentration of atmospheric CO2 from 280 ppm to 390 ppm in 2010 (click here for a video illustration). Approximately one third of the CO2 released by human activity has dissolved in seawater, affecting the carbonate chemistry of the oceans and decreasing ocean pH.

The changes in carbonate chemistry of the oceans will affect cold-water corals in many ways. Firstly, increasing concentrations of dissolved CO2 in the oceans decrease the carbonate saturation of the water, which means there are less carbonate ions available for corals to make their calcium carbonate skeletons. Field and lab studies of tropical corals found that increasing CO2 and assocated pH decline reduce coral skeleton growth by between 3 and 54%, and a similar pattern may be seen in cold-water corals. Indeed, one study found a 0.3 unit decline in pH reduced growth by 56% in Lophelia pertusa. As it has been predicted that by the end of the century pH will have dropped by 0.3 to 0.5 units and temperature increased by a further 1.1 to 6.4 °C, these findings are worrying.

As well as this, ocean acidification could even affect the distribution of cold-water corals by changing the depth of the aragonite saturation horizon. Below this horizon, corals cannot form their calcium carbonate skeletons, as the availability of aragonite (the form of calcium carbonate that scleractinian corals use to form their skeletons) is too low. Furthermore, these skeletons and the skeletons of dead corals that form deep-sea reefs would actually start to dissolve and get worn away by other organisms. By the end of the century, the water chemistry of some oceans and areas will be such that cold-water corals cannot exist there. This would have profound implications not only for the distribution of cold-water corals, but also for the thousands of species which rely on these reefs as habitats. Indeed, any processes affecting the oceanic food web could have far-reaching consequences for these out-of-sight ecosystems.

Future research goals include assessing the influence of increasing CO2 and temperature on cold-water corals from the larval stage right through to reproductively viable adults, and to the ecosystem beyond. Many such studies are in their early stages, with the aim of understanding how these species may respond to environmental change. You can learn more about the experiments being conducted, and conduct your own at the ocean acidification virtual lab.

- The Royal Society (2005) ”Ocean acidification due to increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. Policy document 12/05. Online access.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Online access.